1. Introduction

Lifestyle-related diseases, including insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and cancer, are major global health challenges, often linked to unhealthy diets, inactivity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption [1]. These conditions are leading causes of mortality and morbidity in developed nations [2]. Embracing healthy diets and regular exercise are crucial first steps in managing these conditions, often recommended before resorting to medication. Among dietary components, fruits and green leafy vegetables stand out for their protective effects against heart disease, hypertension [3,4,5,6], and stroke [7]. This benefit is largely attributed to their high nitrate content, a precursor to nitrite and nitric oxide (NO). The positive impacts of these Foods Rich In Nitric Oxide on circulatory health are due to NO’s role in vasodilation and protecting blood vessels from platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion through cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathways [8]. Beyond these well-known functions, NO also plays a role in cGMP-independent and S-nitrosylation-dependent signaling, influencing transcription factors, signal transduction, redox protein modification [9,10,11], mitochondrial function [12,13], and cell apoptosis [14]. These diverse functions explain how foods rich in nitric oxide, specifically dietary nitrate, can help prevent lifestyle-related metabolic, inflammatory, and proliferative disorders. This review will explore NO production through the dietary nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway, its physiological importance, safety, and preventive effects on lifestyle-related diseases, highlighting the significance of foods rich in nitric oxide.

2. Unlocking the Dietary Nitrate-Nitrite-NO Pathway: A Physiological Perspective

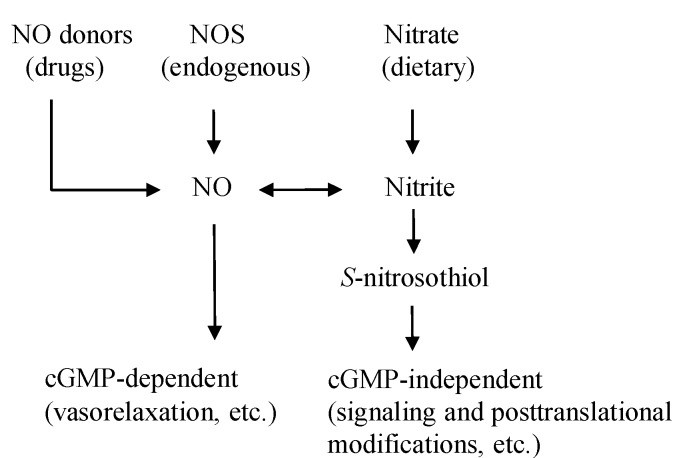

Nitric oxide production in the body isn’t solely dependent on the l-arginine-NO synthase (NOS) pathway. An alternative, NOS-independent route exists: the nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway [15] (Figure 1). Foods rich in nitric oxide such as green leafy vegetables like lettuce, spinach, and beetroot are abundant in nitrate [16] (Table 1). In Western diets, vegetables contribute 60%–80% of daily nitrate intake [17], and consuming these nitric oxide rich foods can significantly increase plasma nitrite levels [18]. A single serving of these vegetables can provide more nitrate than the body endogenously produces via NOS in a day [19].

Figure 1. The Dual Pathways of Nitric Oxide (NO) Production

Figure 1: Illustrating the two primary pathways of nitric oxide (NO) production in the body. NO can be derived from dietary sources, pharmaceutical drugs, and endogenously through the NOS enzyme. This highlights how foods rich in nitric oxide contribute to overall NO availability.

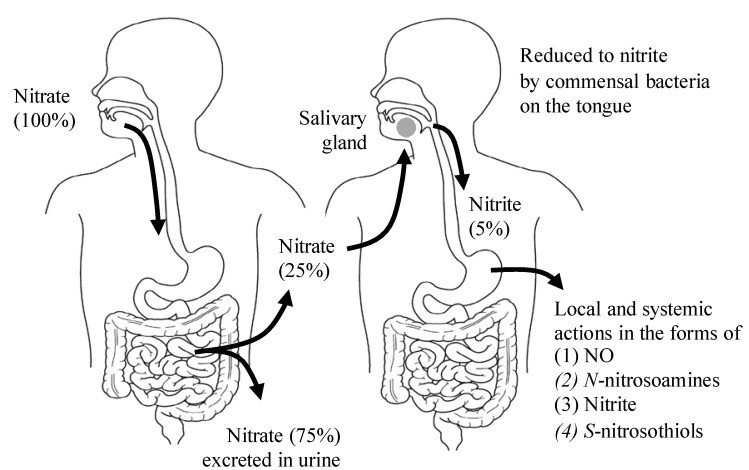

As illustrated in Figure 2, dietary nitrate, from foods rich in nitric oxide, is absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal tract, peaking in plasma within 30–60 minutes post-ingestion [20] (Table 2). Around 25% of absorbed nitrate reaches the salivary glands and is secreted into saliva [21]. Oral bacteria on the tongue then convert this nitrate to nitrite [22]. In the stomach’s acidic environment, some nitrite becomes nitrous acid (NO2− + H+ → HNO2), which decomposes into nitrogen oxides like NO, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3) (2 HNO2 → N2O3 + H2O, N2O3 → NO + NO2) [23]. These nitrogen oxides react with dietary components to form bioactive adducts like S-nitrosothiols and N-nitrosoamines. Notably, NO production in the stomach is enhanced by dietary polyphenols [24] and ascorbic acid [15]. The locally produced NO in the stomach increases mucosal blood flow and mucus thickness, aids in digestion, and acts as a first line of defense against ingested pathogens [25,26]. However, some nitrite escapes stomach protonation and enters systemic circulation, reaching peripheral organs, including skeletal muscles, where it exerts NO-like activity [18] (Figure 2). Plasma nitrite levels are directly linked to salivary nitrate and its conversion to nitrite. Therefore, antibacterial mouthwash use [27] or frequent saliva spitting can reduce plasma nitrite levels [20], impacting the benefits of foods rich in nitric oxide.

Table 1. Nitrate and Nitrite Content in Common Foods

| Food product | Nitrate concentration (mg/100 g) | Nitrite concentration (mg/100 g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Mean | |

| Beets | 275.6 | 168–359 | 1.00 |

| Spinach | 233.3 | 53.5–366 | 0.70 |

| Radishes | 168.0 | 76.4–250 | 0.01 |

| Celery | 154.4 | 31.6–332 | 0.16 |

| Lettuce | 85.0 | 7.9–217.1 | 0.06 |

| Iceberg lettuce | 78.6 | 34.7–108 | 0.02 |

| Mushroom | 59.0 | 1.9–8.5 | 0.80 |

| Cabbage | 57.3 | 19.3–97.6 | 0.24 |

| Broccoli | 39.4 | 2.9–114 | 0.06 |

| Green beans | 38.6 | 16.5–61.1 | 0.05 |

| Strawberries | 17.3 | 10.5–29.3 | 0.20 |

| Banana | 13.7 | 8.8–21.4 | 0.21 |

| Green pepper | 3.3 | 0.8–5.5 | 0.04 |

| Spinach | 741.0 | – | 0.02 |

| Mustard greens | 116.0 | – | 0.003 |

| Salad mix | 82.1 | – | 0.13 |

| Cole slaw | 55.9 | – | 0.07 |

| Broccoli | 39.5 | – | 0.07 |

| Tomato | 39.2 | – | 0.03 |

| Vegetable soup | 20.9 | – | 0.001 |

| Hot dog | 9.0 | – | 0.05 |

| Bacon | 5.5 | – | 0.38 |

| Banana | 4.5 | – | 0.009 |

| Pork tenderloin | 3.3 | – | 0.0 |

| Bacon nitrite-free | 3.0 | – | 0.68 |

| French fries | 2.0 | – | 0.17 |

| Ham | 0.9 | – | 0.89 |

| Fruit mix | 0.9 | – | 0.08 |

| Orange | 0.8 | – | 0.02 |

| Apple sauce | 0.3 | – | 0.008 |

| Ketchup | 0.1 | – | 0.13 |

| Carrots | 0.1 | – | 0.006 |

| Nitrate concentration (mg/L) | Nitrite concentration (mg/L) | ||

| Carrot juice | 27.55 | – | 0.036 |

| Vegetable juice * | 26.17 | – | 0.092 |

| Pomegranate juice | 12.93 | – | 0.069 |

| Cranberry juice | 9.12 | – | 0.145 |

| Acai juice | 0.56 | – | 0.013 |

| Green tea | 0.23 | – | 0.007 |

Table 1: Illustrating the varying concentrations of nitrate and nitrite in different food products. This table highlights which foods rich in nitric oxide contain significant levels of nitrates.

Figure 2. The Entero-Salivary Nitrate-Nitrite-NO Pathway in Detail

Figure 2: A detailed depiction of the entero-salivary nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway. It showcases how dietary nitrate from foods rich in nitric oxide is processed in the body to generate NO, emphasizing the role of saliva and stomach acid.

Table 2. Nitrite, Nitrate, and S-Nitrosothiol Levels After Nitrate Intake

| 0 Min | 30 Min | |

|---|---|---|

| Saliva | Nitrite (μM) | 104 ± 21 |

| Nitrate (mM) | 0.19 ± 0.03 | |

| S-NO (nM) | 25 ± 9.8 | |

| Plasma | Nitrite (μM) | 123 ± 19 |

| Nitrate (mM) | 30 ± 4 | |

| S-NO (nM) | 6.3 ± 1.4 |

Table 2: Showing the change in saliva and plasma levels of nitrite, nitrate, and S-nitrosothiol before and after consuming sodium nitrate. This data supports the rapid increase in nitrate and nitrite levels in the body after consuming foods rich in nitric oxide.

Plasma nitrite from foods rich in nitric oxide is distributed and stored in various tissues. While human data is limited, animal studies confirm that dietary nitrate increases tissue nitrate/nitrite levels (Table 3), contributing to therapeutic effects in disease models. Interestingly, while acute nitrate intake boosts plasma nitrite in both rodents and humans [10,20], chronic intake doesn’t always elevate plasma and tissue nitrite but does increase tissue nitrate and S-nitrosylated products (Table 3). This suggests a potential redox equilibrium shift with long-term intake of foods rich in nitric oxide, leading to nitrite oxidation or reduction into nitrate or S-nitrosylated species. Conversely, diets low in nitrate/nitrite result in decreased plasma and tissue levels, increasing ischemia-reperfusion injuries in animal models [29,30]. This underscores the importance of dietary nitrate intake from foods rich in nitric oxide for maintaining tissue nitrate/nitrite levels and NO-mediated cell protection.

Table 3. Therapeutic Effects of Dietary Nitrate in Animal Models

| Animal Model | Dietary Nitrate | Tissues | Effects of Dietary Nitrate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension rat (uninephrectomized, high-salt diet) | 0.1 mM and 1 mM nitrate/kg/day for 8–11 weeks | Kidney, Heart, Liver | Increased nitrate and nitrosylation, reduced oxidative stress, attenuated renal injury, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and fibrosis | [37] |

| Mice with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension | 0.6 mM, 15 mM, and 45 mM nitrate/L in drinking water for 3 weeks | Lung | Increased nitrite and cGMP, reduced right ventricular pressure and hypertrophy, and pulmonary vascular remodeling | [38] |

| Rat with hypoxic heart damage | 0.7 mM/L nitrate in drinking water for 2 weeks | Heart | Increased nitrate and nitrite, alleviated metabolic abnormalities, improved myocardial energetics | [39] |

Table 3: Illustrating the therapeutic benefits of dietary nitrate supplementation in various animal models. This table highlights how foods rich in nitric oxide can positively impact health outcomes in experimental settings.

Various enzyme and protein-dependent nitrite reductions to NO occur under different conditions, including deoxyhemoglobin [31], deoxymyoglobin [32,33], xanthine oxidase, aldehyde oxidase, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 [34], cytochrome P-450, and mitochondrial nitrite reductases. Unlike NOS-dependent NO production, nitrite reduction is enhanced in low oxygen and acidic environments. Skeletal muscles, rich in nitrite-reducing factors, favor nitrite reduction to NO during exercise-induced hypoxia. This provides an alternative NO source for vasodilation and efficient oxygen use in working muscles [35,36].

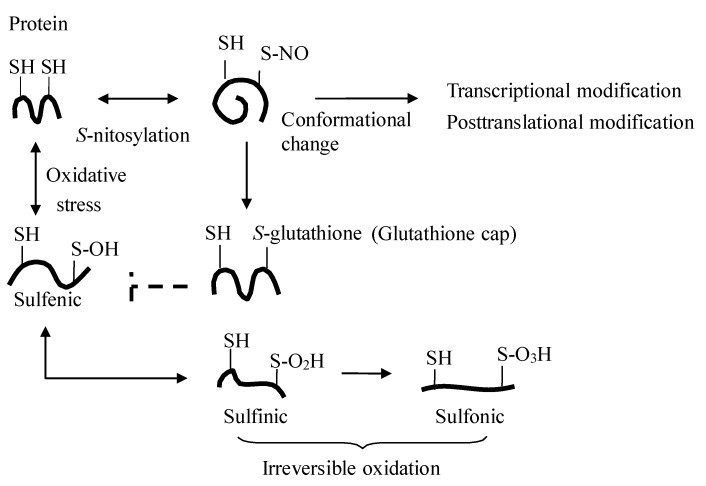

While elevated plasma nitrite from foods rich in nitric oxide influences cGMP production and signaling [10], dietary nitrate/nitrite also signal through cGMP-independent mechanisms like transnitrosylation [40] (Figures 1 and 3). The key question is how NO activity is transported – as S-nitrosothiol, NO, or nitrite – and how transnitrosylation occurs in peripheral organs. Research indicates that oral nitrate intake increases plasma nitrite but not S-nitrosothiol [20] (Table 2). Furthermore, nitrite-mediated transnitrosylation in organs appears to happen directly through nitrite rather than circulating S-nitrosothiol or NO [10].

Studies show that physiological increases in plasma nitrite (0.2–2 μM) enhance S-nitrosothiol in organs, affecting signaling and gene expression related to cGMP, cytochrome P-450, heat shock protein 70, and heme oxygenase-1. Conversely, low nitrate/nitrite diets decrease tissue nitrite levels and reverse these signaling and gene expression changes [10]. These findings suggest that nitrite-induced transnitrosylation may be an alternative in vivo nitrite signaling pathway, protecting proteins from oxidation, modulating transcription, and regulating protein function [9] (Figure 3). Even subtle changes in plasma nitrite levels, such as those after eating foods rich in nitric oxide, can impact tissue S-nitrosothiol levels and cellular processes.

Figure 3. Protein S-Nitrosylation: A Key Regulatory Mechanism

Figure 3: Detailed illustration of protein S-nitrosylation. This process, enhanced by foods rich in nitric oxide, shows how the addition of a NO moiety to protein thiols can regulate protein function and protect cells from oxidative stress.

3. Dietary Nitrate: Safety and Real-World Efficacy

While high nitrate levels in drinking water can cause methemoglobinemia in infants [41], this “blue baby syndrome,” first reported in the 1940s [42], is now believed to be caused by bacterial contamination rather than nitrate itself [43]. Current regulations set maximum nitrate levels in drinking water. The WHO’s Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) for nitrate is 3.7 mg/kg body weight/day. However, typical nitrate intake from food, especially foods rich in nitric oxide, can exceed this. For example, the DASH diet, rich in vegetables and fruits, can lead to nitrate intakes over 1,200 mg/day [28], significantly higher than the WHO’s ADI. Considering that a substantial portion of ingested nitrate is converted to nitrite in saliva and swallowed [22], nitrite intake can also surpass ADI levels. This raises questions about the current safety guidelines and necessitates a re-evaluation of the health effects of dietary nitrate and nitrite from foods rich in nitric oxide [28]. Another concern is the potential for dietary nitrate to contribute to cancer risk due to nitrosamine formation. This aspect will be discussed further in the context of cancer prevention with foods rich in nitric oxide.

4. The Protective Power of Foods Rich in Nitric Oxide Against Lifestyle-Related Diseases

Lifestyle-related diseases are characterized by oxidative stress, inflammation, and reduced NO bioavailability [47]. This imbalance disrupts cellular homeostasis [11,40]. Increasing NO bioavailability, particularly through foods rich in nitric oxide, can improve the intracellular environment via S-nitrosylation [9,40]. Growing evidence suggests that dietary nitrate/nitrite from foods rich in nitric oxide can improve conditions associated with lifestyle diseases by enhancing NO availability [28]. The following sections discuss the benefits of foods rich in nitric oxide for insulin resistance, hypertension, cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury, COPD, cancer, and osteoporosis.

4.1. Combating Insulin Resistance with Nitric Oxide Rich Foods

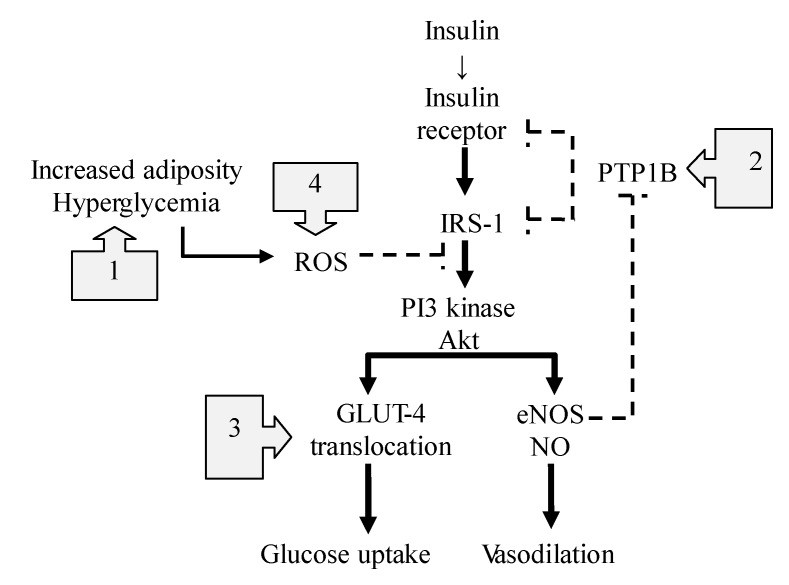

Insulin signaling and endothelial NOS (eNOS) activation share pathways [19,48,49,50,51,52], regulating blood flow and nutrient delivery (Figure 4). Insulin resistance is often linked to impaired NO availability, suggesting an interplay between insulin action and endothelial function [50,53]. NO improves insulin resistance by influencing insulin secretion [54,55], mitochondrial function [56], inflammation [57], insulin signaling [58], and glucose uptake [59]. Insulin-stimulated NO production enhances capillary recruitment and blood flow in muscles, improving glucose disposal [52].

Figure 4. NO’s Impact on the Insulin Signaling Pathway

Figure 4: This diagram illustrates the various ways nitric oxide (NO) influences the insulin signaling pathway. It highlights how foods rich in nitric oxide can support healthy insulin function and combat insulin resistance.

The most significant impact of NO on insulin resistance may be at the post-receptor level of insulin signaling [60] (Figure 4). In diabetic conditions, excess fat and reactive oxygen species (ROS) activate TLR4 pathways [61], disrupting protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation balance in insulin signaling [62]. NO from foods rich in nitric oxide offers several protective mechanisms:

- Reducing Inflammation and ROS: NO suppresses TLR4-mediated inflammation and ROS production by inactivating IκκB/NF-κβ [9,63], key triggers for pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- Enhancing Insulin Effects: NO S-nitrosylates protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTPB1), enhancing insulin sensitivity [52]. PTPB1 dephosphorylates insulin receptors and substrates, reducing insulin effectiveness. NO counteracts this by suppressing PTPB1 activity.

- Facilitating Glucose Uptake: NO-dependent nitrosylation of GLUT4 improves glucose transporter translocation to the cell membrane, enhancing glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity [65].

- Mitigating Mitochondrial ROS: Excess nutrients can cause mitochondrial superoxide and ROS overproduction. NO inhibits mitochondrial ROS by S-nitrosylating mitochondrial respiratory chain complex 1, improving mitochondrial efficiency [12].

Studies support the therapeutic potential of dietary nitrate from foods rich in nitric oxide for improving insulin resistance in humans and animals [65,66,67,68]. Since insulin resistance is linked to metabolic and endothelial dysfunction, leading to hypertension and atherosclerosis [50,51,53,69,70], enhancing NO availability through foods rich in nitric oxide is a promising strategy for prevention and treatment [71].

4.2. Lowering Hypertension with Foods Rich in Nitric Oxide

Increased fruit and vegetable consumption is linked to lower cardiovascular disease risk [72,73,74]. The DASH diet, rich in vegetables, fruits, and low-fat dairy, is known to lower blood pressure, attributed to calcium, potassium, polyphenols, fiber, and low sodium content [75,76]. However, the high nitrate content of these foods rich in nitric oxide also increases plasma nitrate and nitrite [77], which are precursors to NO. Evidence suggests that nitrate/nitrite in fruits and vegetables contributes significantly to their cardiovascular benefits [29,33,78,79,80,81,82,83] and in humans [31,84,85,86].

Numerous studies show that dietary nitrate from foods rich in nitric oxide reduces blood pressure in humans [87,88,89]. Research has demonstrated that dietary sodium nitrate, in amounts found in 150-250g of nitrate-rich vegetables, reduces diastolic blood pressure in healthy individuals [84]. Beetroot juice, a prime example of foods rich in nitric oxide, has been shown to lower blood pressure and improve flow-mediated dilation, effects attributed to nitrite conversion from nitrate [86]. Beetroot juice consumption increases plasma nitrite and cGMP, leading to vasodilation and blood pressure reduction [85]. Daily beetroot juice intake over four weeks has been shown to lower blood pressure and improve endothelial function and arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients [90]. Dietary nitrite has also shown promise in treating vascular aging by improving aortic pulse wave velocity and endothelium-dependent dilation through reduced oxidative stress and inflammation [91]. These findings suggest that foods rich in nitric oxide may be beneficial for preventing and treating age-related hypertension.

Furthermore, hypertension contributes to ischemic heart disease and cardiac remodeling. Dietary nitrite supplementation has been shown to improve heart function and reduce cardiac fibrosis in hypertensive mice by increasing cardiac nitrite, nitrosothiol, and cGMP levels [92]. While acute effects of dietary nitrate are well-studied, more research is needed on long-term effects and in hypertensive patients to fully leverage the potential of foods rich in nitric oxide.

4.3. Protecting Against Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury with Nitric Oxide Rich Foods

During cardiac ischemia, ATP depletion disrupts ion pumps and causes calcium overload, damaging cell membranes. Reperfusion further injures cells due to mitochondrial ROS production, enzyme denaturation, and membrane destruction. NO availability is compromised during ischemia/reperfusion, exacerbating injury [30,95].

Nitrite, nitrate, and NO-related compounds are naturally present in blood and tissues. Cardiac tissue nitrite levels are higher than plasma levels [96], serving as an extravascular NO pool during hypoxia [97]. Dietary nitrate from foods rich in nitric oxide increases cardiac tissue nitrite and S-nitrosothiol levels, reducing oxidative stress and preventing cardiac injury in animal models [37]. Nitrite stored in the heart and liver enhances tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury [33].

While eNOS overexpression can protect against myocardial infarction [98], NO’s protective effects during ischemia/reperfusion largely depend on nitrite reserves and their reduction to NO when NOS activity is limited. Tissue S-nitrosothiols, signaling molecules, increase through nitrite reduction during NOS inhibition, hypoxia, and acidosis [97], highlighting tissue nitrite as an on-demand NO source. Factors like deoxyhemoglobin, deoxymyoglobin, and mitochondrial enzymes reduce nitrite in tissues [99,100]. Dietary nitrate/nitrite supplementation maintains higher nitrite and nitroso compound levels in cardiac muscle, reducing infarct size after ischemia/reperfusion in animal models [29]. These findings indicate that foods rich in nitric oxide provide cardioprotective nitrate/nitrite.

Nitrite’s protective effects are mediated by S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex 1, reducing mitochondrial ROS and apoptosis [101]. Nitrite also influences intracellular calcium handling, reducing calcium entry and increasing sarcoplasmic reticulum uptake, mitigating calcium overload during ischemia/reperfusion [102].

Interestingly, while antioxidant supplements alone have shown mixed results in preventing cardiovascular disease [103,104,105], fruits and vegetables, foods rich in nitric oxide, have consistently shown preventive effects against coronary heart disease [3,4,5,6,106]. A balanced intake of fruits and vegetables, providing both nitrate/nitrite and vitamins, may be more effective for heart health than antioxidant supplements alone, making foods rich in nitric oxide a crucial dietary component.

4.4. Managing Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) with Diet

COPD is a lifestyle-related disease linked to smoking and chronic bronchitis [107]. Healthy diets are crucial in COPD prevention [108]. High intakes of whole grains, polyunsaturated fatty acids, nuts, and omega-3 fats, and low intakes of red/processed meats and sugary drinks are associated with lower COPD risk.

Cured meats, high in nitrite, have been linked to increased COPD risk [109,110,111]. Nitrite can generate reactive nitrogen species, potentially causing lung damage [111]. However, cured meats contribute minimally (4.8%) to daily nitrite intake, while saliva accounts for 93% [114]. Nitrite levels in processed meats have also significantly decreased since the 1970s [115]. Therefore, focusing solely on cured meats might not fully represent the complex relationship between nitrite and COPD.

Conversely, fruits and vegetables, foods rich in nitric oxide, along with n-3 fatty acids and vitamins, show beneficial effects on lung function and COPD risk [108,116,117,118,119,120,121,122]. Nitrate and nitrite from foods rich in nitric oxide are reduced to NO, forming S-nitrosothiols rather than nitrosamines, especially with vitamins C and E present [28,123,124]. Dietary nitrate doesn’t significantly elevate gastric or serum nitrite concentrations [125].

The entero-salivary pathway of dietary nitrate from foods rich in nitric oxide enhances NO availability through S-nitrosothiols and transnitrosylation. Dietary nitrate, unlike direct nitrite infusion, reduces oxygen consumption and resting metabolic rate, improving mitochondrial function [126]. This metabolic benefit is crucial for COPD patients who often experience malnutrition due to increased metabolic rate.

NO’s role in COPD is complex. NO from foods rich in nitric oxide and constitutive NOS may be protective through S-nitrosothiol mechanisms, including bronchial relaxation and anti-inflammatory effects [127]. However, iNOS-mediated NO may be pro-inflammatory in COPD [128].

Studies show that dietary nitrate from beetroot juice improves exercise performance and reduces blood pressure in COPD patients [130,131]. More large-scale studies are needed, but current evidence suggests potential benefits of foods rich in nitric oxide for COPD management.

4.5. Nitric Oxide Rich Foods and Cancer: A Nuanced Perspective

In the stomach, nitrite from saliva and potentially foods rich in nitric oxide can form N-nitrosoamines [132], some of which are carcinogenic [133,134,135]. Red and cured meats, containing added nitrite, have been linked to increased cancer risk. However, methodological concerns exist regarding high nitrosatable amine doses in animal studies and physiological differences between animals and humans [136].

In the stomach, nitrosonium ions (NO+) from nitrite can form S-nitrosothiols and N-nitrosamines. S-nitrosothiol formation is favored in acidic conditions and is kinetically faster, especially with vitamins C, E, and polyphenols present in fruits and vegetables, foods rich in nitric oxide. These compounds also neutralize nitrosating agents. This might explain why achlorhydria patients and non-vegetarians consuming cured meats are at higher gastric cancer risk [137,138,139,140,141,142].

However, linking dietary nitrite directly to cancer is complex. Most daily nitrate intake (90%) comes from vegetables, foods rich in nitric oxide, and nitrite primarily from saliva (5.2–8.6 mg/day), not cured meats (0.05–0.6 mg/day) [136]. Recent studies and expert committees have found no clear link between dietary nitrate and increased cancer risk [143,144].

Large-scale studies show inverse associations between fruit intake and upper gastrointestinal and lung cancer, and between fiber intake and liver cancer. Vegetable intake, from foods rich in nitric oxide, is inversely associated with colorectal cancer risk, suggesting no increased risk of cancer from vegetable consumption [145].

Chronic inflammation, however, can induce iNOS and generate high NO levels [22,146,147], potentially causing mutagenesis [148,149]. NO can have both protective and harmful effects on cancer depending on location and concentration [150,151].

Antioxidant supplements alone haven’t consistently shown cancer prevention benefits and may even increase mortality risk [104]. While NO’s role in cancer is complex, dietary nitrate from plant-based foods rich in nitric oxide appears to have inhibitory effects on cancer risk, possibly synergizing with other nutrients in these foods.

4.6. Strengthening Bones Against Osteoporosis with Dietary Nitrates

Lifestyle factors impact bone health and density, potentially leading to osteoporosis [152,153,154,155,156]. NOS-mediated NO plays a role in bone cell function [157]. iNOS-induced NO inhibits bone resorption and formation in inflammatory conditions, contributing to osteoporosis [158]. eNOS, conversely, is crucial for osteoblast activity and bone formation; eNOS knockout mice exhibit osteoporosis [159].

Estrogen’s bone benefits are partly mediated by NO-cGMP pathways [160], suggesting NO donor therapy as a potential alternative to estrogen. Organic nitrate NO donors show benefits in experimental and clinical osteoporosis [161,162,163]. High fruit and vegetable intake, foods rich in nitric oxide, is linked to protective effects against osteoporosis [164,165,166]. Further research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in osteoporosis prevention, but current evidence points to the potential benefits of foods rich in nitric oxide for bone health.

5. Conclusion: Embracing Foods Rich in Nitric Oxide for a Healthier Lifestyle

Dietary nitrate from fruits and vegetables, foods rich in nitric oxide, delivers NO activity through various forms, impacting health via the entero-salivary pathway. While the full scope of diet-derived NO in lifestyle diseases is still being researched, incorporating foods rich in nitric oxide as part of a balanced diet offers potential health benefits. The synergistic effects of nitrate with other nutrients in vegetables make foods rich in nitric oxide a valuable nutritional approach to preventing and managing lifestyle-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from Josai University and thank the editors and reviewers for their insightful feedback.

Author Contributions

Jun Kobayashi: Manuscript writing. Kazuo Ohtake and Hiroyuki Uchida: Manuscript review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] WHO. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2003, 916, i-viii, 1-149.

[2] Yusuf, S.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; Dans, T.; MacKay, J.; Jablonsky, L.; Yusuf, S.; Czernichow, S.; Al-Khawaja, I.; Rangarajan, S.; et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364, 937-952.

[3] Dauchet, L.; Amouyel, P.; Dallongeville, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2588-2593.

[4] He, F.J.; Nowson, C.A.; MacGregor, G.A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet 2006, 367, 320-326.

[5] Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A.; Ellinger, S.; Haller, D.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Frickmann, E.; Maxiner, A.; Meier, T.; Muhlenbruch, K.; et al. Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637-669.

[6] Crowe, F.L.; Lloyd-Webber, M.; Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Travis, R.C. Fruit and vegetable intake and mortality from ischaemic heart disease: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Oxford study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 26, 171-180.

[7] Johnsen, S.P.; Overvad, K.; Sorensen, H.T.; Larsen, B.B.; Pedersen, O.; Tjonneland, A. Intake of fruit and vegetables and the risk of ischemic stroke in a cohort of Danish men and women. Stroke 2003, 34, e45-e49.

[8] Lundberg, J.O.; Gladwin, M.T.; Weitzberg, E. Strategies to increase nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 623-641.

[9] Hess, D.T.; Stamler, J.S. NO- and SNO- signaling pathways. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a011439.

[10] Bryan, N.S.; Wang, L.; Feelisch, M.; Loscalzo, J.; Stamler, J.S. Nitrite is a signaling molecule and regulator of gene expression in mammalian tissues. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 673-679.

[11] Stamler, J.S.; Toone, E.J. S-Nitrosylation in biology and medicine. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1-3.

[12] Brown, G.C. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial respiration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1411, 351-369.

[13] участием, J.L.; Kim-Han, J.S.; Lancaster, J.R., Jr.; Pfeiffer, S.; Zweier, J.L. Nitric oxide inhibits mitochondrial respiration through reversible binding to cytochrome c oxidase. Implications for hypoxic cell injury and regulation of respiration. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 27583-27587.

[14] Mannick, J.B.; Hausladen, A.; Liu, L.; Hess, D.T.; Zeng, M.; Miao, Q.X.; Kane, L.S.; Gow, A.J.; Stamler, J.S. Fas-induced caspase denitrosylation. Science 1999, 284, 651-654.

[15] Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Gladwin, M.T. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 156-177.

[16] Hord, N.G.; Tang, Y.; Bryan, N.S. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1S-10S.

[17] Gangolli, S.D.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Feron, V.J.; Janzowsky, C.; Koeman, J.H.; Speijers, G.J.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Walker, R.; Wishnok, J.S. Nitrate and nitrite. In Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995; pp. 1-387.

[18] Benjamin, N.; O’Driscoll, G.; Haydock, S.; Pearl, V.; Catapano, A.L.; Mann, G.E.; Dongen, R.V.; Feelisch, M. Vascular effects of dietary nitrate (as beetroot juice) in healthy volunteers. Lancet 2001, 357, 149-151.

[19] Sindler, A.L.; Little, J.P.; Cutler, M.J.; Blackwell, T.A.; Credeur, D.P.; Fernhall, B.; Kanaley, J.A. Beetroot juice improves in