Introduction

Herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) are increasingly popular worldwide, including in the United States, as people seek to enhance their health and well-being. Among these, supplements marketed as “food supplements for liver” or for liver health are gaining traction, promising detoxification, support, and improved liver function. However, alongside the rising use of HDS, there’s a growing concern about liver injury induced by these products. Recent data indicates that HDS are now implicated in a significant percentage of liver toxicity cases in the US. This article aims to delve into the complexities surrounding food supplements for the liver, exploring their potential benefits, the risks of liver injury, and crucial considerations for consumers to ensure liver health and safety.

The issue of HDS-related hepatotoxicity is a serious and evolving challenge. While some supplements may offer health benefits, it’s essential to recognize that they are not without potential risks. This article will examine the current landscape of food supplements for the liver, drawing upon research and expert consensus from a symposium sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the National Institutes of Health. We will explore the types of liver injury associated with HDS, the specific supplements and ingredients of concern, and the critical steps needed to safeguard public health.

The Landscape of Herbal and Dietary Supplements

The term “Herbal and Dietary Supplements” (HDS) encompasses a wide range of products, from traditional herbal remedies to vitamins, minerals, and performance enhancers. These are generally available over-the-counter and often taken without medical supervision. In the context of “Food Supplement For Liver,” this category includes products marketed to support liver function, detoxify the liver, or improve overall liver health.

In the United States, dietary supplements are regulated as foods, not drugs, under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. This classification means that unlike pharmaceutical drugs, HDS do not require pre-market approval for safety and efficacy. Manufacturers are responsible for ensuring their products are safe, but the burden of proof falls on the FDA to demonstrate a supplement is unsafe before it can be removed from the market. This regulatory framework differs significantly from that of prescription drugs, and it’s crucial for consumers to understand these distinctions, especially when considering supplements marketed for sensitive organs like the liver.

Population surveys reveal that a significant portion of the US adult population consumes dietary supplements. Sales in the supplement industry have grown dramatically, indicating increasing consumer interest in these products. While vitamins and minerals remain popular, specialized supplements, including those for liver health, are also contributing to this growth. It is vital for consumers to have access to reliable information about these products to make informed decisions regarding their health. Resources like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) websites, including the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), offer valuable information on various supplements.

The Increasing Concern of Liver Injury from HDS

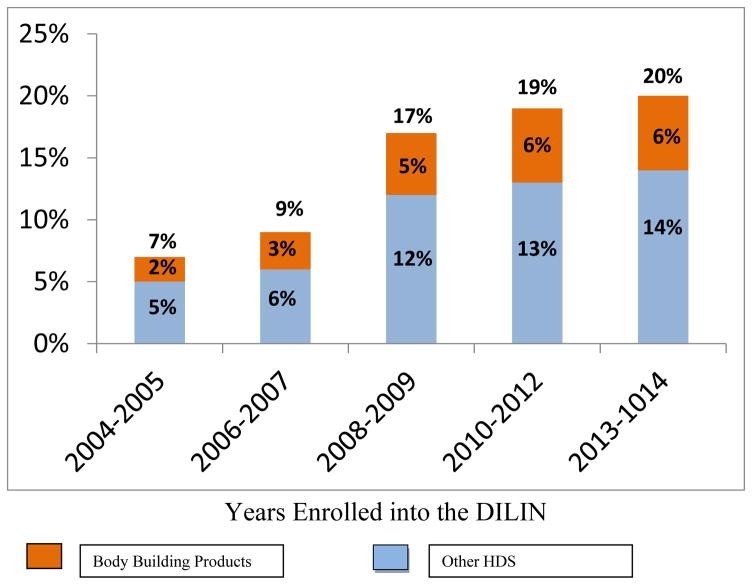

While the popularity of “food supplement for liver” and other HDS rises, so does the evidence of liver injury associated with their use. Data from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN), a prospective study funded by the NIH, highlights this growing trend. Initially, HDS accounted for a smaller percentage of drug-induced liver injury cases, but this proportion has steadily increased over the years, reaching a concerning 20% in recent data. This increase underscores the importance of understanding the potential risks associated with these supplements, particularly those marketed for liver health, as they may paradoxically cause liver damage.

European registries also report an increase in HDS-related liver injury cases, reflecting a global trend. Interestingly, the prevalence varies geographically, with significantly higher rates reported in some Asian countries compared to others. This variation may be due to differences in the types of supplements used, regulatory practices, or reporting mechanisms. However, the overall trend indicates that liver injury from HDS is a worldwide health concern.

Population-based studies offer further insight into the incidence of HDS-related liver injury. A study in Iceland estimated that a notable proportion of acute liver injury cases were attributable to HDS, suggesting that the risk is not negligible and warrants careful consideration, especially for individuals using “food supplement for liver” products without proper guidance.

Common HDS and “Food Supplement for Liver” Associated with Liver Injury

Analysis of cases reported to the DILIN study reveals patterns in the types of HDS associated with liver injury. Bodybuilding supplements, often containing anabolic steroids, constitute a significant portion of cases. These agents, frequently marketed illicitly, can cause a distinctive type of cholestatic liver injury. While not strictly categorized as “food supplement for liver,” some performance-enhancing supplements might be misleadingly marketed with liver support claims, adding to the confusion for consumers.

Excluding anabolic steroids, a substantial number of HDS-related liver injury cases are linked to complex mixtures sold under various brand names, many of which fall under the umbrella of “food supplement for liver” or wellness products. These products often contain multiple ingredients, making it challenging to pinpoint the specific component responsible for liver toxicity.

Among the ingredients implicated in liver injury, green tea extract stands out as a single herbal product of concern. Multi-ingredient nutritional supplements (MINS) represent a significant category, often containing a combination of vitamins, minerals, botanicals, and proprietary blends. Products marketed for weight loss, energy enhancement, and general wellness, including some “food supplement for liver” formulations, frequently fall into this category and have been linked to liver injury. The complexity of these mixtures and the lack of clear labeling can make it difficult for consumers and healthcare professionals to assess the risks accurately.

Green Tea Extract: A Closer Look at Liver Risks

Green tea extract (GTE) is a popular ingredient in many health supplements, including some “food supplement for liver” products, due to its purported antioxidant and weight loss benefits. While green tea as a beverage is generally considered safe, concentrated green tea extracts have been linked to cases of acute hepatitis. This highlights the importance of understanding that even natural ingredients, when concentrated and consumed in supplement form, can pose risks.

Despite claims of weight loss and health benefits, scientific evidence supporting these claims for GTE is limited. However, the market for GTE-containing supplements, including those marketed for liver health or detoxification, remains strong. The link between GTE and liver injury came as a surprise, as initial expectations were that it would be relatively safe. Since the first reports, numerous cases of acute liver injury attributed to GTE have been documented, raising concerns about its widespread use in supplements.

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) assessed reports of liver injury linked to GTE but did not initially recommend a warning label, citing a lack of conclusive evidence and data on the quality of implicated preparations. However, subsequent research and continued reports of liver injury have solidified the association between GTE and hepatotoxicity. Studies analyzing products implicated in liver injury have found catechins, components of GTE, even in products not explicitly labeled as containing green tea, suggesting potential contamination or undisclosed ingredients.

The mechanism of GTE-induced liver injury is not fully understood, but high doses of catechins, particularly epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a major component of GTE, are known to be hepatotoxic in animal models. While the doses of EGCG in reported human cases may not always seem excessively high, the liver injury is believed to be an idiosyncratic reaction in susceptible individuals. This means that the risk is not solely dose-dependent and can occur unpredictably in certain people.

Other herbal products, beyond GTE, have also been linked to liver injury, although often with less conclusive evidence or alternative explanations like contamination. Contamination of HDS with toxins, other herbs, or even undeclared pharmaceutical drugs is a significant concern. Herbal products like black cohosh, kratom, and others have been implicated in liver injury reports, but establishing a definitive causal link is often challenging due to issues of product purity, labeling accuracy, and the complexity of herbal mixtures.

The OxyElite Pro® Outbreak: A Case Study in Supplement Risk

The outbreak of acute hepatitis linked to the weight loss product OxyElite Pro® serves as a stark example of the potential dangers of poorly regulated supplements. This incident, which began in Hawaii and spread to the continental US, involved previously healthy individuals developing severe liver injury after taking the product. OxyElite Pro®, marketed for weight loss and muscle building, highlights the risks associated with multi-ingredient supplements, particularly those with undisclosed or novel ingredients.

The clinical presentation of OxyElite Pro®-related liver injury was characterized by acute hepatitis-like symptoms, including jaundice, fatigue, and elevated liver enzymes. Severe cases required liver transplantation, and fatalities occurred, emphasizing the seriousness of the potential harm. The implicated ingredient was suspected to be aegeline, a compound added to the product formula shortly before the outbreak.

Chemical analysis confirmed the presence of aegeline in implicated batches of OxyElite Pro®, but the exact mechanism of its liver toxicity remains unclear. Aegeline is derived from the bael tree, used in traditional medicine, but the form used in OxyElite Pro® may have been synthetic and contained toxic byproducts. This case underscores the risks of adding novel or poorly studied ingredients to supplements and the potential for serious adverse events.

The OxyElite Pro® incident led to product withdrawal and regulatory scrutiny, but it also exposed vulnerabilities in the supplement industry’s oversight and the challenges in ensuring product safety. It serves as a cautionary tale for consumers considering “food supplement for liver” and other complex supplements, emphasizing the need for caution and informed decision-making.

Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Jaundice: A Distinct Liver Injury Pattern

Anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS), often used illicitly for bodybuilding and performance enhancement, represent another category of HDS associated with liver injury. While these are not typically marketed as “food supplement for liver,” it’s important to understand their distinct liver toxicity profile, especially as some individuals might use them alongside other supplements marketed for liver support, compounding potential risks.

AAS, particularly 17-α-alkylated steroids, are known to cause a characteristic cholestatic jaundice. This type of liver injury differs from the acute hepatitis-like pattern seen with many other HDS. AAS-induced jaundice typically presents with prolonged and intense jaundice, often with minimal elevation in liver enzymes initially, followed by a rise in alkaline phosphatase. Liver biopsies show “bland cholestasis,” a pattern distinct from other forms of liver injury.

Although AAS-induced jaundice can be severe and prolonged, with bilirubin levels reaching high levels, liver failure is relatively uncommon. The injury is usually self-limiting, resolving after cessation of steroid use. Management primarily involves supportive care and symptomatic treatment for pruritus (itching). Corticosteroids are not effective in treating this type of liver injury.

The mechanism of AAS-induced cholestasis is not fully understood but is thought to involve impaired bile flow at the canalicular level. The pattern resembles benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC), a genetic condition affecting bile secretion. However, genetic studies in patients with AAS-induced jaundice have not consistently identified mutations in genes associated with BRIC, suggesting a different underlying mechanism.

Diagnosing HDS-Induced Liver Injury

Diagnosing liver injury from HDS, including “food supplement for liver” products, relies on a comprehensive assessment, including patient history, medication and supplement use, and exclusion of other causes of liver disease. There are no specific diagnostic tests for HDS-induced liver injury, and its presentation can mimic various liver conditions. The possibility of product contamination or misidentification of ingredients further complicates diagnosis.

The typical clinical presentation of HDS-associated liver injury is acute hepatitis, characterized by elevated liver enzymes (aminotransferases) and often jaundice. Immunoallergic or autoimmune features are less common. The onset of symptoms usually occurs within a few months of starting the supplement, and resolution typically takes a few weeks to months after stopping the product. Fatal outcomes are possible, but the exact fatality rate is difficult to determine due to underreporting and unknown supplement usage prevalence.

Liver biopsy can be helpful in excluding other liver diseases and providing characteristic histological findings. In AAS-related liver injury, “bland cholestasis” is a distinctive feature. For other HDS, liver biopsy findings may be less specific but can still aid in diagnosis and prognosis.

Resources like the LiverTox website (http:/www.LiverTox.nih.gov) provide valuable information on the hepatotoxicity of various HDS and clinical examples of liver injury. A structured diagnostic approach is crucial for accurately identifying HDS-induced liver injury and differentiating it from other liver diseases.

Chemical and Toxicological Analysis: Unraveling HDS Complexity

Ensuring the quality and safety of “food supplement for liver” and other HDS requires robust chemical and toxicological analysis. Current FDA regulations mandate good manufacturing practices (GMP) for supplements, requiring manufacturers to verify the identity, purity, strength, and composition of their products. However, the specific analytical methods for verification are not strictly defined.

Botanical authentication, involving macroscopic and microscopic examination, is a traditional method for verifying plant-based ingredients. However, these methods have limitations, particularly with processed or complex mixtures. Chemical standardization, using techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), is commonly employed to quantify marker compounds and create analytical “fingerprints” of botanical ingredients. These methods can help assess batch-to-batch consistency but can be expensive and require pure reference standards.

Genetic fingerprinting using DNA technologies is an emerging field for botanical authentication. However, the quality of DNA extracted from commercially available plant material can be variable, posing challenges for analysis. Statistical techniques like Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can be applied to analyze phytochemical fingerprints and compare samples to authenticated reference materials.

Toxicological analysis is crucial for identifying hepatotoxic components within HDS. Conventional toxicology involves in vitro and in vivo testing to assess cellular and organ toxicity. However, the complexity of HDS mixtures makes it challenging to isolate and test individual components effectively. Toxicological analysis of HDS requires methods to separate products into their components and evaluate their toxicity, both individually and in combination, to understand potential synergistic or additive effects.

Future Directions: Research and Regulation for Safer HDS

Addressing the growing problem of liver injury from “food supplement for liver” and other HDS requires a multi-pronged approach involving research, regulation, and public awareness. Key research priorities include elucidating the mechanisms of HDS-induced liver injury, identifying toxic ingredients, and developing better predictive models for toxicity testing. Clinical research needs to focus on standardized causality assessment methods and collecting well-characterized cases to identify risk factors and improve management strategies.

Regulatory improvements are crucial to enhance the safety of HDS. Current regulations have been criticized as inadequate, with limited pre-market scrutiny and challenges in monitoring adverse events. Proposed regulatory changes include mandatory FDA registration of HDS, stricter labeling requirements including full ingredient disclosure and adverse event reporting, and prohibiting unsubstantiated structure-function claims.

Public awareness campaigns are essential to educate consumers about the potential risks and benefits of HDS, including “food supplement for liver” products. Consumers should be advised to consult healthcare professionals before using supplements, especially those with pre-existing liver conditions or those taking medications. Improved adverse event reporting systems are needed to capture data on HDS-related liver injury more effectively and inform regulatory actions.

Conclusion

Liver injury from herbal and dietary supplements, including products marketed as “food supplement for liver,” is a significant and growing concern. While some supplements may offer potential health benefits, the risks of liver injury, particularly from complex multi-ingredient products and certain herbal extracts like green tea extract, should not be underestimated. Consumers need to be aware of the regulatory landscape, the limitations of current oversight, and the importance of making informed decisions about supplement use.

Collaboration among clinicians, researchers, regulators, and the supplement industry is essential to address this challenge. Priorities include enhancing research to understand mechanisms of liver injury, improving analytical methods for product quality control, strengthening regulatory frameworks, and raising public awareness. Ultimately, the goal is to ensure that consumers can make safe and informed choices regarding “food supplement for liver” and other HDS, protecting their liver health and overall well-being.

References

[List of references from the original article – to be included here, formatted according to a standard citation style like APA or MLA]

Disclaimer: This article provides general information and should not be considered medical advice. Consult with a healthcare professional before using any food supplement for liver or making decisions about your health.