Clover Food plots are a cornerstone for landowners and gamekeepers aiming to support thriving wildlife populations, particularly whitetail deer and turkeys. Across diverse regions, from the northern reaches of Missouri to Manitoba, and from the Dakotas eastward to Michigan and Quebec, clover has proven its worth. While its benefits are universally acknowledged, managing clover in the Southern United States presents unique challenges. To navigate these complexities, we turn to Austin Delano, Southern Field Services Manager and Head of Research and Development for BioLogic, a renowned expert in wildlife food plots, for his insights into maximizing clover food plot success, especially in the South.

Understanding the Value of Clover Food Plots

For those dedicated to wildlife management, clover stands out as a highly beneficial plant to incorporate into their land. In many parts of the country, especially the Midwest and northward, clover is considered essential for a robust food plot strategy. This perspective should extend to the South as well, even though cultivation might require more nuanced approaches compared to regions with cooler, more humid climates. Clover thrives in these cooler conditions, making the Midwest, the northern U.S., and Canada ideal environments for these legumes. While planting schedules and maintenance practices vary geographically, the nutritional value and palatability of clover remain consistent, making it a valuable asset for whitetail management everywhere. Different clover varieties offer specific traits tailored to various management goals and environmental conditions, reinforcing clover’s indispensable role in a comprehensive wildlife program due to its extensive benefits.

Perennial white clovers are particularly prized for their long-term contribution to wildlife nutrition, offering years of high-protein, palatable forage. While annual and biennial white clover varieties exist, perennial types provide sustained benefits. Red clovers, known for their resilience across a wider range of conditions, are also an option, though they typically are not as attractive to whitetails as white clover varieties. For optimal results, many experts recommend using a blend of different clover varieties, possibly incorporating other perennials like alfalfa, trefoils, or chicory. Such blends not only extend the period of palatability but also enhance the plot’s resilience against specific environmental challenges that might hinder single-variety stands.

Even in the heat of the South, perennial clover plots can flourish, provided there is sufficient rainfall. Established perennial clover can withstand extreme heat and drought by going dormant and then vigorously recovering once moisture returns. This resilience is attributed to the robust root system of well-established clover in healthy soil, enabling it to endure challenging conditions.

Moisture is a critical success factor for any wildlife planting, and clover is no exception. Regions receiving 25 to 30 inches of annual rainfall are generally suitable for perennial clover varieties. In drier or sandy areas, incorporating deep-rooted perennials like alfalfa and chicory into clover blends can significantly improve stand survival.

Long-Term Management and Soil Health for Clover

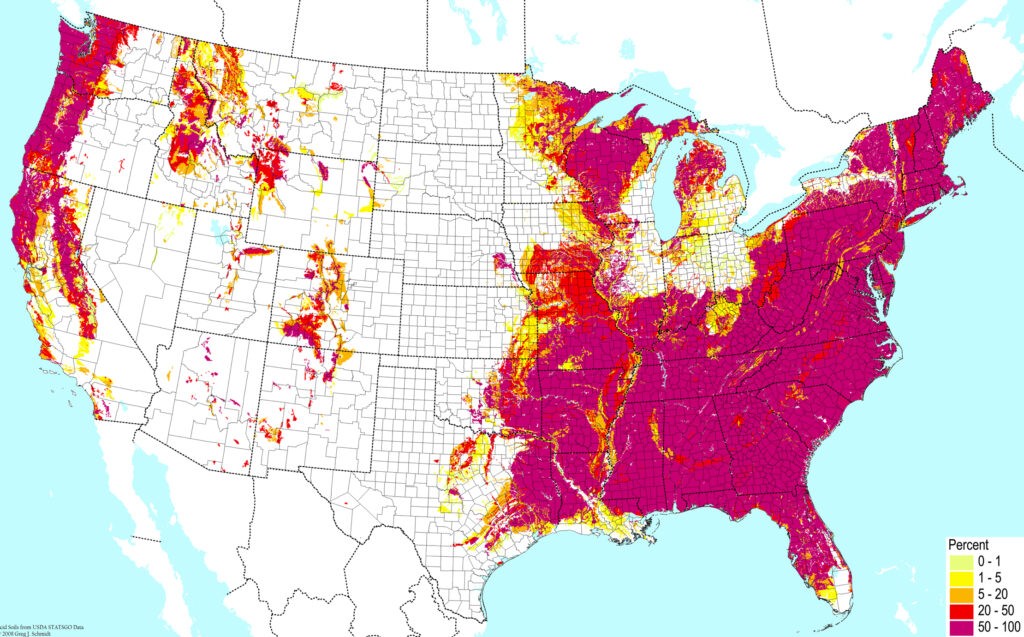

When properly maintained and planted in soil with a near-neutral pH, perennial clover plots can last for six to eight years or even longer. However, in more acidic soils, which are common in the South and eastern seaboard, the longevity might be reduced to three to five years due to the need for periodic lime application to counteract soil acidity. Depending on soil type and initial pH, liming may be necessary to maintain optimal growing conditions for clover. Rotating with an annual crop before replanting clover in the same area can also be beneficial for soil health and clover productivity.

White clovers spread effectively through stolons, which are horizontal stems growing along the soil surface. These stolons develop nodes where roots form, creating new “daughter plants” that eventually replace the original seedlings. Varieties that produce more stolons, typically the small-leaved types, exhibit greater persistence.

Regeneration from seed is another important aspect of clover longevity. If grazing pressure is moderate and mowing is not excessive, clover plants will flower and produce seeds. This natural reseeding process is particularly valuable in regions with dry summers, such as the South and West, contributing to the long-term viability of the clover stand. Large-leaved clover types, like Non-Typical varieties, benefit from less frequent mowing or limited grazing to allow them to mature and produce seed. However, mowing remains a crucial part of clover maintenance, especially during cooler growing seasons.

Small-leaved clover varieties, in contrast, thrive under frequent grazing or mowing. Large-leaved varieties grow taller and more upright compared to their small-leaved counterparts, which tend to have thicker stolons and stronger root systems. Large-leaved types produce fewer stolons and may not persist as long as medium and small-leaved varieties, making them more susceptible to being uprooted by heavy grazing.

Medium-leaved types, such as White Dutch clover, offer an intermediate set of characteristics, performing well in a broader range of conditions. Small-leaved types are most tolerant of consistent grazing pressure. While they do not grow as tall as large-leaved clovers, their abundance of small leaves and numerous stolons make them excellent choices for areas with high deer densities.

Choosing the right clover type necessitates considering growing conditions, deer density relative to plot acreage, and available maintenance resources (mowing, herbicide application, fertilization, overseeding). For instance, if frequent mowing is not feasible or deer density is low, large-leaved varieties might be preferable. Conversely, for areas where frequent mowing is possible and deer density is high, small-leaved clover types are more suitable. The exposure of stolons to sunlight, encouraged by regular mowing in small-leaved types, promotes daughter plant production, leading to a dense, long-lasting stand.

It’s important to note that large-leaved clover does not necessarily equate to higher tonnage per acre. The yield potential across different white clover types (from large to small-leaved) is comparable when each variety is properly managed.

To ensure a continuous food source, consider planting perennial clover acreage in stages, avoiding replanting entire areas at once. Replanting necessitates field preparation and establishment, which can leave a field unproductive for a significant portion of a growing season. Staggered planting ensures that some clover plots are always mature and productive.

Planting and Establishment of Clover Food Plots

Planting perennial clover is straightforward: prepare a suitable seedbed and broadcast the seed at the recommended rate. The seed should be covered very lightly, ideally no more than ¼ inch deep. Using a cultipacker or roller after broadcasting improves seed-to-soil contact, which is crucial for germination.

Traditionally, perennial clovers are planted in the spring in northern regions, in spring or early summer in mid-latitude areas, and in late summer or early fall in the South. These timings align with periods of optimal moisture availability, maximizing crop survival. However, planting times can be somewhat flexible, especially in northern and transitional zones. The key is to plant early enough to allow sufficient root system development before dormancy. Perennial clovers typically need 45 to 60 days to establish a robust root system, ensuring their perennial nature and regrowth after dormancy. In Minnesota, for example, late summer planting has become increasingly popular due to reduced weed competition after the summer weed cycle. Regardless of timing, adequate moisture remains the primary determinant of planting success.

Maintaining Healthy and Productive Clover Food Plots

Maintaining perennial clover plots is less demanding than often perceived, although timing is crucial, especially in the South. One significant challenge in the South and along the eastern seaboard is soil acidity. These regions tend to have more acidic soils compared to the Midwest and northern states, necessitating attention to soil pH. Soil pH greatly influences nutrient availability, and acidic conditions can bind essential nutrients, making them inaccessible to plants, while also potentially elevating micronutrient levels to toxic concentrations for clover. Legumes, including clover, are particularly sensitive to acidic soils. Therefore, conducting a soil test and applying lime to achieve a pH between 6.5 and 7.0 is vital for clover establishment and health.

Fertilizer selection is another critical aspect of clover maintenance. Clover can utilize both atmospheric nitrogen, fixed through its root nodules, and mineral nitrogen from synthetic fertilizers. Typically, a fertilizer blend without nitrogen (N) is recommended for established clover plots, such as 300 to 350 pounds of 0-20-20 per acre. A balanced fertilizer containing nitrogen (e.g., 10-10-10) can be used at planting to aid initial establishment, but nitrogen should be avoided afterward. Adding nitrogen to established clover encourages weed and grass competition and inhibits clover’s natural nitrogen-fixing ability. Fertilize at planting and annually thereafter, ideally based on soil test recommendations.

Mowing frequency and height significantly impact clover productivity. Frequent mowing during spring promotes white clover growth by encouraging stolon production and denser stands. Infrequent mowing allows larger leaf development but reduces stolon production and new growth. Frequent mowing, removing only a portion of the plant height each time, restricts plant height but increases stolon survival and stem density, resulting in a thicker, healthier, and more attractive stand for wildlife.

In the South, mowing timing is particularly critical. During hot and dry periods, frequent mowing should be avoided, and allowing clover to produce seed heads might be beneficial. In cooler, moist conditions, more frequent mowing is advantageous. A general guideline for hot, dry months is the “rule of thirds”—never remove more than 1/3 of the plant’s height when mowing.

Mixing chicory and/or alfalfa with clover can enhance food plot resilience, especially in drier conditions. These perennials have deeper root systems than clover, providing forage during dry periods. Chicory, in particular, thrives in hot, dry weather, offering a nutritious food source when clover growth slows.

Herbicide use may be necessary to manage weed competition in clover plots. Grass-specific herbicides, often clethodim-based, are commonly used a couple of times per growing season. While mowing helps control broadleaf weeds, herbicides like 2-4-DB are available for broadleaf weed control in clover, though caution is needed to avoid using 2-4-D, which will harm clover. Maintaining a healthy, dense clover stand is often the best defense against weed encroachment, often negating the need for broadleaf herbicides.

Overseeding perennial clover plots every few years is a beneficial practice. Overseeding at about ¼ of the original planting rate helps fill in bare spots from various causes, introduces new seedlings, and rejuvenates the stand. This practice can extend the productive life of clover plots to ten years or more, maintaining their value as a consistent food source for wildlife.

Clover food plots are an invaluable component of any comprehensive wildlife management program, offering substantial benefits whether in the North or South. Proper establishment and maintenance, tailored to regional conditions, ensure their long-term success and contribution to healthy wildlife populations.

Join our weekly newsletter or subscribe to GameKeepers Magazine. Your source for information, equipment, know-how, deals and discounts to help you get the most from every hard-earned moment in the field.

[