WHAT IS FAKE FOOD?

WHAT IS FAKE FOOD?

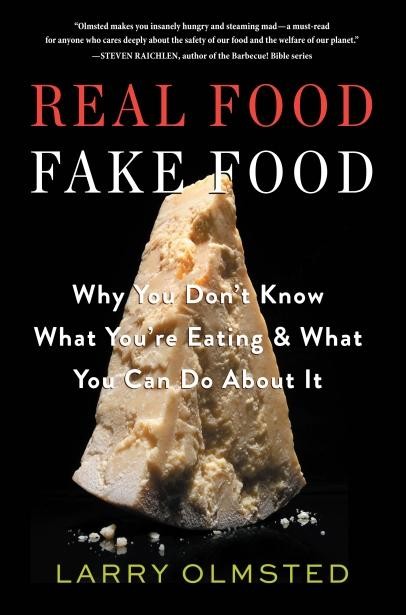

It’s a universal frustration: feeling cheated, especially when it comes to something as essential as the food we eat. As Bee Wilson aptly put it, “Being cheated over food is one of the universal human experiences.” In today’s complex food landscape, understanding what constitutes real versus Fake Food is more critical than ever. This article delves into the world of “fake food,” exploring its various forms, the motivations behind it, and how consumers can navigate this increasingly deceptive terrain.

To begin, let’s define what we mean by “Real Food” and “Fake Food.” Real Food, in its simplest form, is authentic and unadulterated – it is exactly what it claims to be. A prime example is the North Atlantic lobster, often associated with Maine. These lobsters are easily identifiable in their whole form and are inherently difficult to fake, even compared to similar species. They are wild-caught, never farmed, and free from artificial enhancements like hormones or antibiotics. They are, simply put, lobsters – and their delicious, rich flavor is undeniable. Whether enjoyed in a fine dining establishment or a casual beachside setting, the experience of savoring a genuine Maine lobster is consistently satisfying.

However, not all Real Food is as readily apparent. Imagine two glasses side-by-side: one containing authentic red Burgundy wine, the other a counterfeit California “Burgundy.” Visually, distinguishing between them might be challenging for the average person. Yet, upon tasting, the disparity becomes clear. Even without extensive wine expertise, one can discern the imitation due to its inability to replicate the nuanced quality of genuine Burgundy.

This illustrates a crucial aspect of Real Food: authenticity goes beyond mere appearance. A bottle of authentic French Burgundy wine, for example, carries a promise of specific origin and quality. It signifies a wine made exclusively from 100% Pinot Noir grapes, sourced from a region renowned for its Pinot Noir, where viticulture traditions stretch back millennia. Furthermore, strict regulations and quality assessments govern Burgundy production, ensuring that only grapes from top-rated vineyards within the region can bear the prestigious name.

In stark contrast, a California “Burgundy” might cynically exploit the reputation of its French counterpart to mislead consumers. Lacking the quality to compete honestly, it relies on brand confusion. It might be a blend of various inexpensive grapes, with its composition changing from batch to batch, bearing little resemblance to genuine Burgundy in terms of quality or character.

The spectrum of fake food is broad, and not all imitations are created equal. Food fraud manifests in distinct ways, which can be broadly categorized into illegal counterfeits, utter impostors, and legal and gray-area counterfeits.

Illegal Counterfeits: The Criminal Underbelly of Food Fraud

Illegal counterfeiting in the food industry mirrors the scams prevalent in luxury goods. Think of fake Nike sneakers or Gucci bags – it’s about creating unlicensed copies of branded, high-value products. In the food world, this often involves directly replicating premium items, frequently wines, olive oils, and certain seafood.

A notable example occurred in 2014 when Italian authorities uncovered a massive fraud operation, seizing thirty thousand bottles of counterfeit Brunello, Chianti Classico, and other prestigious Italian DOCG wines. DOCG, Italy’s highest wine classification, is intended to “guarantee” quality and origin. However, these counterfeiters filled bottles with inexpensive wines, affixed fake DOCG seals, and meticulously replicated labels to mimic high-end brands. These fraudulent bottles infiltrated retail stores, bars, and restaurants before the scheme was exposed. Subsequent raids uncovered hundreds more bottles of fake Barolo, another premium Italian wine, packaged similarly. In a particularly audacious case, two fraudsters amassed over two million euros by repackaging cheap wine as highly sought-after French Burgundy, selling each bottle for over six thousand dollars by even faking vintage years.

While these criminal acts are alarming, this type of outright illegal counterfeiting is, in some ways, a less pervasive issue compared to other forms of food fraud. It’s akin to petty theft; consumers become victims by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. While law enforcement can address these crimes, they represent a smaller facet of the broader fake food problem. However, certain food categories, like olive oil and seafood, are more susceptible to this type of criminal activity, warranting closer attention. Ultimately, protecting oneself from illegal counterfeits is challenging, as even careful label reading may not reveal the deception.

Utter Impostors: Substituting the Unthinkable

Moving beyond simple economic fraud, we encounter “utter impostors” – the most egregious form of food fakery. This involves replacing a food product entirely with an unrelated, often cheaper, and sometimes dangerous substitute. While illegal counterfeiters at least use a cheaper version of the genuine product (like cheap wine for expensive wine), utter impostors abandon any pretense of using the real ingredient.

A chilling example of this occurred in 1986 in Italy, where winemakers substituted toxic methyl alcohol for grape-derived alcohol, resulting in over twenty fatalities. This highlights the potentially lethal consequences of utter impostor fraud.

Historically, product substitution has been a recurring problem. In 18th-century London, merchants commonly passed off chopped, roasted, and dyed leaves as Chinese black tea, with “green tea” being an even more dangerous concoction dyed with copper. A more recent and widespread example is the European horsemeat scandal, where horsemeat was substituted for beef, particularly in processed foods like frozen lasagna, across the European food supply chain.

The insidious nature of utter impostor fraud lies in its undetectability by the average consumer. One cannot visually distinguish ground leaves in a teabag or chopped meat in lasagna. This visual opacity is a recurring theme in fake food. Despite advancements in food testing, utter impostor fraud remains surprisingly prevalent due to limited oversight and inspection of the global food supply. Many everyday foods are produced, imported, labeled, and sold with minimal scrutiny. In certain food categories, this type of fraud poses a significant public health risk. Consider herbal teas, for instance, which have been identified as particularly vulnerable to adulteration.

While often criminal, utter impostor fraud is more systemic. However, consumer awareness and informed purchasing choices can offer some protection. Knowing which foods are most at risk and sourcing them from reputable vendors are crucial steps. Furthermore, stronger government oversight and stricter penalties for perpetrators are necessary to deter this dangerous form of food fraud. Currently, penalties for substituting foods, even with hazardous substances, are often lenient, effectively decriminalizing such practices. While counterfeit wine is a relatively small market segment, counterfeit fish, in many cases, is the market, highlighting the scale of the problem.

Legal and Gray-Area Counterfeits: Deception Within the Law

The most ethically complex category of fake food falls into the realm of “legal and gray-area counterfeits.” This category involves situations where manufacturers legally mislead consumers into believing they are purchasing a superior or different product than what they are actually getting. Examples like California “Burgundy” perfectly illustrate this. While technically legal, these practices exploit consumer expectations and blur the lines of authenticity.

The crux of the issue lies in differing philosophies. If one believes that businesses should be free to operate as long as they technically adhere to often inadequate laws, even if their behavior is deceptive or harmful, then “legal fake foods” might be considered acceptable. However, a more ethical perspective argues that intentionally misleading consumers, even legally, constitutes fraud.

Consider a hypothetical scenario: Imagine if the Russian government, aiming to bolster domestic industries, legalized the production of “American” products under established brand names, regardless of origin or quality. Suddenly, a Russian-made “Microsoft Office” lacking key applications or a low-quality sedan masquerading as a “Cadillac Escalade” could legally exist.

While legal within Russia, American manufacturers like Cadillac and Microsoft would be outraged, and the U.S. government would likely protest vehemently. Exporting these Russian-made fakes to most developed nations would be impossible due to counterfeit laws. However, the domestic Russian market and similar markets could sustain such practices.

The primary victim in this scenario would be the Russian consumer, deceived into believing they are purchasing the quality and features associated with genuine Microsoft or Cadillac products. This constitutes economic fraud. Meanwhile, the Russian “Microsoft” and “Cadillac” producers profit, and the authentic American companies suffer lost sales and reputational damage. If a wealthy oligarch, desiring a genuine Cadillac Escalade for its prestige and quality, unknowingly buys a fake, the consequences are amplified. He suffers economic fraud, potential safety risks from the inferior vehicle, and the reputation of Cadillac as a brand is tarnished. From the perspective of American CEOs, these Russian products would undoubtedly be considered fake, despite their legal status in Russia, mirroring the legality of “California Champagne” in the U.S.

This highlights a critical point: Real Foods are often defined not just by recipes but by specific processes and origins. Growing the same onion or corn variety in different locations yields vastly different results due to terroir. Similarly, a Pinot Noir wine made in Oregon, even using identical vines and winemaking techniques as in Burgundy, will never be truly Burgundy because of the distinct soil and climate. Burgundy, Parmigiano-Reggiano, and Cadillac are, in essence, brands representing specific styles and high quality linked to origin. While other producers can create similar products, they shouldn’t be allowed to use the protected brand names associated with those regions or consortiums.

The U.S. trademark system differs from those in France and Italy, where collective ownership of trademarks for regional products is common. In the U.S., trademarks are typically owned by individual companies, like Cadillac. Parmigiano-Reggiano, however, is protected by a consortium of producers.

A real-world example of this gray-area counterfeiting is unfolding with pizza. Grimaldi’s, a Brooklyn pizzeria renowned for its coal-fired ovens and distinctive New York-style pizza, has built a strong brand reputation over decades. Its success has led to a national chain. However, the owners discovered a carbon-copied Grimaldi’s pizzeria in Shanghai, complete with identical signage and staff uniforms bearing the slogan “I’m gonna make you a pizza you can’t refuse.” The Shanghai imposter capitalized on Grimaldi’s established reputation, particularly among Chinese tourists familiar with New York City guidebooks. Instead of creating their own pizza brand, they chose to directly steal Grimaldi’s identity. While many winemakers produce Burgundy-style wines without misusing the Burgundy name, those who do are typically selling inferior imitations. The real Grimaldi’s initiated a lawsuit against a former employee involved in the Chinese “clone.”

The legality of such blatant brand theft depends on trademark laws in the respective countries. In the U.S., terms like “Champagne” have been deemed generic, losing trademark protection. The outcome for Grimaldi’s in China hinges on whether “Grimaldi’s” is recognized as a protected trademark under Chinese law.

Regardless of legalities, such actions are ethically reprehensible. Hijacking a brand’s reputation, known as “riding the coattails,” is inherently wrong, even if it doesn’t immediately cause economic damage. The principle of honesty and fair competition is violated.

Furthermore, producers might usurp existing product names to simplify consumer understanding. Swiss consumers readily understand “Gruyère” cheese. However, a U.S. cheesemaker producing a Gruyère-style cheese faces a challenge in conveying its nature without falsely labeling it as Gruyère. Using terms like “imitation” or “style” offers a transparent solution. “Imitation Gruyère” clearly indicates it is not genuine Gruyère, while “Kansas City-style barbecue” signals it’s not from Kansas City. These qualifiers provide honest context. Therefore, using modifiers like “imitation Kobe” or “Parmesan-style” is recommended. Even if these imitations are high quality, they are not the authentic products they mimic. (Interestingly, even the term “counterfeit” can be used honestly, as seen with “Genuine Counterfeit Cuban Cigars,” clearly indicating a Cuban-style cigar made elsewhere.)

However, using geographic qualifiers like “domestic” or “California” can be misleading. “California Champagne” is inherently inaccurate as true Champagne must originate from the Champagne region of France. Such labels place an unfair burden on consumers to decipher the nuances of food origins. Products should not be advertised in ways that contradict established definitions.

Similarly, terms like “natural,” “pure,” or “100% something” often fall into a gray area. These terms lack strict legal definitions and are frequently used to deceive consumers. Manufacturers exploit this ambiguity, applying these labels to products in confusing and sometimes absurd ways. In a lawsuit between hot dog giants Ball Park and Oscar Mayer, Kraft defended its “100 percent pure beef” label on Oscar Mayer hot dogs, arguing that it only meant the beef component was pure beef, not that the entire hot dog was solely beef. Such labeling practices are deliberately misleading and uninformative.

While laws generally prohibit “misleading” marketing, proving deception is a high legal bar, often requiring case-by-case lawsuits. Kobe beef exemplifies this gray area. While most “Kobe beef” sold in the U.S. is fake, its legal status as a “legal counterfeit” persists due to the lack of specific laws prohibiting its use. Consumer lawsuits against such food fraud are rare and often require class-action status to be viable, leaving many restaurants free to make unsubstantiated menu claims.

Masa Noda, a trademark attorney specializing in Kobe beef protection, emphasizes the ethical dimension of this issue: “When people hear ‘Kobe beef,’ they think, ‘Oh that’s something good,’ so there is definitely consumer deception going on, no doubt. But once you learn that natural means nothing, organic means nothing, you learn that you need to go only with what you trust. But the more you learn, the less you trust.” His efforts to protect Kobe beef through trademark law highlight the ongoing battle against food fraud driven by principle, aiming to prevent consumer deception.

It is important to note that the European Union takes a stricter stance against imitation labeling. EU regulations for geographic indications prohibit the use of protected names even with modifiers like “imitation,” “style,” or “type,” arguing that such terms still constitute “misuse, imitation, or evocation” of the protected name. This contrasts with the more lenient U.S. approach and underscores the ongoing global debate surrounding food authenticity and consumer protection.

In conclusion, understanding the nuances of fake food is crucial for consumers seeking authentic and high-quality products. By recognizing the different categories of food fraud – from illegal counterfeits to utter impostors and legal gray-area imitations – and by being informed and discerning shoppers, individuals can better navigate the complexities of the modern food system and make choices that prioritize both quality and integrity.