Is Sourdough A Fermented Food? Absolutely! This guide, brought to you by FOODS.EDU.VN, explores the fascinating world of sourdough, a naturally fermented bread that offers a unique taste and health benefits. Delve into the science behind sourdough fermentation, discover the diverse microbial communities involved, and learn why sourdough is a great choice for your gut and overall well-being. Get ready to explore this age-old baking method with improved properties of bread and nutritional advantages.

1. What Makes Sourdough a Fermented Food? The Science Explained

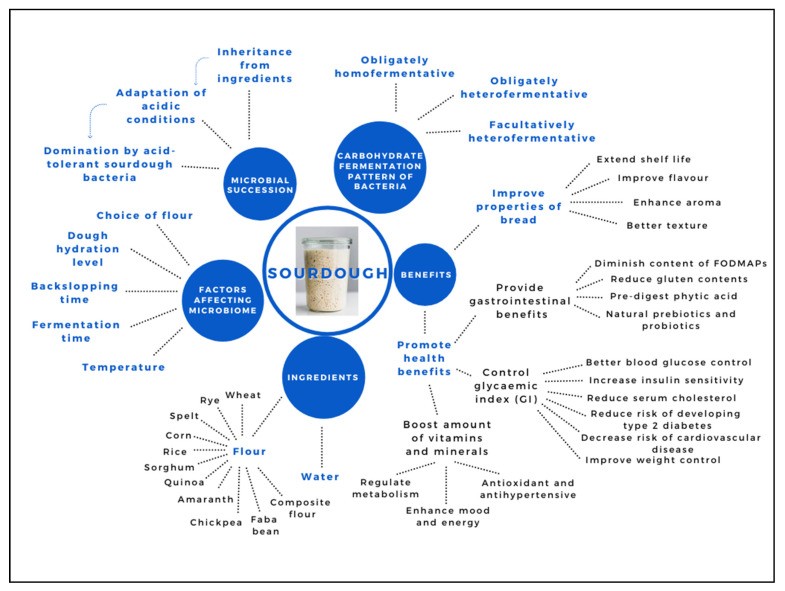

Yes, sourdough is indeed a fermented food. The fermentation process is what gives sourdough its distinct tangy flavor and unique characteristics. But what exactly does that mean?

Fermentation is a metabolic process in which microorganisms like bacteria and yeast convert carbohydrates (sugars and starches) into acids, gases, or alcohol. In the case of sourdough, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and wild yeasts naturally present in flour work together to ferment the dough. This process breaks down complex carbohydrates, producing lactic acid and acetic acid, which contribute to the characteristic sour taste and aroma of sourdough. This fermentation also produces carbon dioxide, which leavens the bread.

1.1. The Sourdough Starter: A Living Ecosystem

The heart of sourdough fermentation lies in the sourdough starter, also known as a “mother” or “levain.” This is a living culture of flour and water teeming with wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria. The starter acts as a miniature ecosystem where these microorganisms thrive, consuming the sugars in the flour and producing the acids and gases that give sourdough its unique qualities.

The microbial composition of a sourdough starter is incredibly complex and can vary depending on factors like:

- Flour type: Different flours harbor different types and quantities of microorganisms.

- Water source: Minerals in the water can influence the growth of certain bacteria.

- Environment: The temperature and humidity of the baking environment can affect the microbial activity.

- Feeding schedule: How often the starter is fed with fresh flour and water influences the balance of microorganisms.

Sourdough Starter Bubbles

Sourdough Starter Bubbles

1.2. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB): The Key Players

Lactic acid bacteria are the dominant microorganisms in sourdough starters, and they play a crucial role in the fermentation process. These bacteria produce lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the dough, creating a tangy flavor and inhibiting the growth of undesirable microorganisms. Some common LAB found in sourdough include Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Lactobacillus brevis.

1.3. Wild Yeasts: The Leavening Agents

In addition to LAB, wild yeasts are also essential for sourdough fermentation. These yeasts produce carbon dioxide, which leavens the dough, giving it its airy texture. Unlike commercial baker’s yeast, which is typically a single strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sourdough starters contain a diverse range of wild yeast species, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida humilis.

2. What are the 5 Different Types of Sourdough? Exploring Sourdough Varieties

While all sourdough relies on wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria for fermentation, different methods and ingredients lead to distinct types of sourdough, each with unique characteristics. Understanding these variations can help you choose the best sourdough for your taste and baking needs. The three main sourdough categories are:

2.1. Type I: Traditional Sourdough

Traditional sourdough, also known as “backslopping,” involves continuous propagation by regularly refreshing the starter with fresh flour and water. This method maintains a stable culture over time. Type I sourdough can be further divided into:

- Type Ia: Pure culture sourdough starters of different origins.

- Type Ib: Spontaneously fermented and refreshed daily.

- Type Ic: Originating from tropical countries with higher fermentation temperatures.

2.2. Type II: Industrial Sourdough

Type II sourdough uses adapted cultures inoculated industrially as dough acidifiers. This approach ensures consistency and optimization for large-scale production.

2.3. Type III: Dried Sourdough

Type III sourdough is dried for easy storage and utilization. This form is convenient for commercial applications, maintaining the sourdough flavor profile in a shelf-stable product.

2.4. Type 0: Pre-doughs or Sponge Doughs

Some researchers also consider Type 0 sourdough, which includes pre-doughs or sponge doughs with added baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae).

2.5. Gluten-Free Sourdough

Gluten-free sourdough uses non-wheat flours like rice, sorghum, or a blend, often combined with starches and gums to mimic the texture of wheat-based sourdough. These sourdoughs may require specific starter maintenance techniques and hydration levels to achieve the desired rise and crumb structure.

| Sourdough Type | Characteristics | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | Traditional, continuous propagation | Home baking, artisanal bread making |

| Type II | Industrially inoculated, adapted cultures | Large-scale bread production |

| Type III | Dried for easy storage | Commercial baking, shelf-stable products |

| Type 0 | Pre-doughs with baker’s yeast | Hybrid sourdoughs, enhanced flavor development |

| Gluten-Free | Uses non-wheat flours | Gluten-free baking, dietary restrictions |

3. Exploring 5 Ways Sourdough Benefits Your Health

Beyond its unique flavor and texture, sourdough offers several health benefits thanks to the fermentation process and the microorganisms involved.

3.1. Improved Digestion

Sourdough fermentation can improve digestion in several ways:

- Reduced FODMAPs: Fermentation breaks down FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), short-chain carbohydrates that can cause digestive issues in some people.

- Gluten Reduction: The fermentation process can break down gluten proteins, making sourdough easier to digest for individuals with mild gluten sensitivities.

- Phytic Acid Reduction: Sourdough fermentation helps break down phytic acid, a compound that can inhibit the absorption of minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium.

3.2. Enhanced Nutrient Availability

By reducing phytic acid, sourdough fermentation increases the bioavailability of minerals, making them easier for your body to absorb. This can help improve your intake of essential nutrients.

3.3. Blood Sugar Control

Sourdough bread generally has a lower glycemic index (GI) than conventionally leavened bread. This means it causes a slower and more gradual rise in blood sugar levels, which can be beneficial for individuals with diabetes or insulin resistance.

3.4. Gut Health Support

Sourdough contains prebiotics, non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial bacteria in your gut. These prebiotics can help promote a healthy gut microbiome, which is essential for overall health.

3.5. Improved Flavor and Texture

The fermentation process produces a variety of flavor compounds, giving sourdough its characteristic tangy taste and complex aroma. The acids produced during fermentation also help to soften the gluten in the dough, resulting in a more tender and chewy texture.

| Health Benefit | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Improved Digestion | Reduces FODMAPs, breaks down gluten, and neutralizes phytic acid |

| Enhanced Nutrient Availability | Decreases phytic acid, improving mineral absorption |

| Blood Sugar Control | Lower glycemic index (GI) results in a slower rise in blood sugar levels |

| Gut Health Support | Contains prebiotics, feeding beneficial gut bacteria |

| Improved Flavor & Texture | Produces tangy taste, complex aroma, and a softer, chewier texture due to fermentation byproducts |

4. Diving Deeper: The Microbial Communities in Sourdough

Sourdough starters are complex ecosystems that host a diverse array of microorganisms. Understanding these microbial communities is key to understanding the unique characteristics of sourdough.

4.1. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)

These are the dominant bacteria in sourdough and are responsible for the production of lactic acid, which gives sourdough its tangy flavor and inhibits the growth of undesirable microorganisms.

Common Species:

- Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis: Highly adapted to sourdough environments.

- Lactobacillus plantarum: Versatile and commonly found in various sourdoughs.

- Lactobacillus brevis: Contributes to flavor and acidification.

4.2. Yeasts

Yeasts produce carbon dioxide, which leavens the dough and gives it its airy texture.

Common Species:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Also known as baker’s yeast, found in some sourdoughs.

- Candida humilis: Contributes to the flavor profile.

- Kazachstania exigua: Another wild yeast species that helps with leavening.

4.3. Factors Affecting Microbial Diversity

- Flour Type: Wheat, rye, spelt, and other flours influence the microbial composition. Rye flour, with its higher amylase content, provides more readily fermentable sugars for LAB.

- Fermentation Temperature: Different microbes thrive at different temperatures, affecting the final microbial profile.

- Backslopping: The process of refreshing the starter by adding flour and water.

| Microorganism | Role | Common Species |

|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid Bacteria | Produces lactic acid, tangy flavor, inhibits undesirable microbes | L. sanfranciscensis, L. plantarum, L. brevis |

| Yeasts | Produces carbon dioxide, leavening | S. cerevisiae, Candida humilis, K. exigua |

| Flour | Wheat, Rye, Spelt… Influence the microbial compostion | |

| Temperature | Affects the final microbial profile | |

| Backslopping | Refreshing the starter by adding flour and water |

5. Crafting Your Own: A Simple Sourdough Recipe

Want to experience the magic of sourdough fermentation firsthand? Here’s a basic recipe to get you started:

Ingredients:

- 1 cup (120g) active sourdough starter

- 2 1/2 cups (300g) bread flour

- 1 1/4 cups (300ml) warm water

- 1 teaspoon (6g) salt

Instructions:

- Mix: In a large bowl, combine the starter, flour, and water. Mix until a shaggy dough forms.

- Rest: Cover the bowl and let the dough rest for 30 minutes (autolyse).

- Knead: Add the salt and knead the dough for 8-10 minutes until smooth and elastic.

- Bulk Fermentation: Place the dough in a lightly oiled bowl, cover, and let it ferment for 4-6 hours at room temperature, folding the dough every 1-2 hours.

- Shape: Gently shape the dough into a round or oblong loaf.

- Proof: Place the shaped loaf in a well-floured banneton basket or a bowl lined with a floured kitchen towel. Cover and refrigerate overnight (8-12 hours).

- Bake: Preheat your oven to 450°F (232°C) with a Dutch oven inside. Carefully remove the hot Dutch oven, place the loaf inside, score the top with a sharp knife or razor blade, and cover with the lid.

- Bake: Bake for 20 minutes with the lid on, then remove the lid and bake for another 25-30 minutes, or until the crust is golden brown and the internal temperature reaches 200-210°F (93-99°C).

- Cool: Let the bread cool completely on a wire rack before slicing and enjoying.

Tips:

- Use a kitchen scale for accurate measurements.

- Adjust the fermentation time based on your starter’s activity and the room temperature.

- Experiment with different flours to create unique flavors.

- For more detailed instructions and troubleshooting tips, visit FOODS.EDU.VN.

| Step | Instructions | Time/Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| Mix | Combine starter, flour, and water | Until shaggy dough forms |

| Rest | Autolyse | 30 minutes |

| Knead | Add salt and knead until smooth and elastic | 8-10 minutes |

| Bulk Fermentation | Ferment with folds | 4-6 hours at room temperature |

| Shape | Gently shape the dough | |

| Proof | Refrigerate overnight | 8-12 hours |

| Bake | Preheat oven with Dutch oven, bake with lid, then without lid | 450°F (232°C), 20 mins with lid, 25-30 mins without |

| Cool | Let cool completely on a wire rack before slicing |

6. Why Sourdough? Addressing Common Concerns

Sourdough, while celebrated for its unique flavor and potential health benefits, often raises questions among consumers. Here are some common concerns addressed:

6.1. Is Sourdough Gluten-Free?

No, traditional sourdough is not gluten-free. It is made with wheat flour, which contains gluten. However, the fermentation process can break down some of the gluten proteins, potentially making it easier to digest for those with mild gluten sensitivities, though not suitable for those with celiac disease. Gluten-free sourdough is made with non-wheat flours.

6.2. How Sour Should Sourdough Taste?

The sourness of sourdough can vary depending on several factors:

- Fermentation Time: Longer fermentation times generally result in a more sour flavor.

- Temperature: Lower fermentation temperatures favor the production of acetic acid, which contributes to a sharper, more vinegary sourness.

- Starter Composition: The specific strains of LAB in your starter can influence the type and amount of acids produced.

6.3. Is Sourdough Healthier Than Other Breads?

Sourdough offers several potential health benefits compared to conventionally leavened breads, including improved digestion, enhanced nutrient availability, and a lower glycemic index. However, it’s important to remember that all bread should be consumed in moderation as part of a balanced diet.

6.4. How to Store Sourdough Bread?

To keep your sourdough loaf fresh:

- Store it in a bread box or a paper bag at room temperature.

- Avoid storing it in the refrigerator, as this can dry it out.

- For longer storage, slice the loaf and freeze it in an airtight container.

| Concern | Answer |

|---|---|

| Is Sourdough Gluten-Free? | No, unless made with gluten-free flours; fermentation may reduce some gluten but not safe for celiacs. |

| How Sour Should It Taste? | Varies with fermentation time, temperature, and starter composition; can range from mild to very tangy. |

| Is It Healthier? | Yes, it offers improved digestion, nutrient availability, and lower GI compared to some other breads, but moderation is key. |

| How to Store? | Store in a bread box or paper bag at room temperature; freeze sliced for longer storage, avoid refrigerating to prevent drying out. |

7. Optimizing Your Sourdough for Health and Flavor: Advanced Techniques

For those looking to take their sourdough baking to the next level, consider these advanced techniques:

7.1. Adjusting Hydration

Hydration refers to the ratio of water to flour in your dough. Higher hydration doughs (70-80% water) result in a more open crumb and a chewier texture. Lower hydration doughs (60-65% water) are easier to handle and produce a tighter crumb.

7.2. Controlling Fermentation Temperature

Fermentation temperature significantly impacts the flavor and texture of sourdough. Lower temperatures (68-72°F or 20-22°C) promote acetic acid production, resulting in a more sour flavor. Higher temperatures (75-80°F or 24-27°C) favor lactic acid production, leading to a milder, more yogurt-like flavor.

7.3. Using Different Flours

Experimenting with different flours can add complexity and depth to your sourdough.

- Rye Flour: Adds a nutty flavor and a darker color.

- Whole Wheat Flour: Provides a more robust flavor and increased fiber content.

- Spelt Flour: Offers a slightly sweet and nutty flavor with a lighter texture.

| Technique | Effect | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusting Hydration | Higher hydration: Open crumb, chewier texture; Lower hydration: Tighter crumb, easier handling | Adjust based on flour type and desired outcome |

| Controlling Temp | Lower temps: More sour flavor; Higher temps: Milder, yogurt-like flavor | Monitor starter activity and adapt proofing times |

| Using Different Flours | Rye: Nutty flavor, darker color; Whole Wheat: Robust flavor, increased fiber; Spelt: Sweet, light texture | Adjust hydration and fermentation times based on flour characteristics |

8. Sourdough Around the World: A Culinary Journey

Sourdough bread is enjoyed in various forms around the world, each region adding its unique twist to the ancient baking method. Here are a few notable examples:

- San Francisco Sourdough (USA): Known for its distinctive tangy flavor and chewy texture, often attributed to the unique microbial composition of the local sourdough starters.

- Pain au Levain (France): A rustic sourdough bread made with a natural starter, often characterized by a complex flavor and a slightly dense crumb.

- Roggenbrot (Germany): A dark, dense rye bread made with sourdough, known for its hearty flavor and long shelf life.

- Borodinsky Bread (Russia): A traditional sourdough rye bread flavored with coriander and molasses, offering a complex and slightly sweet flavor profile.

| Bread Name | Region | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| San Francisco Sourdough | USA | Tangy flavor, chewy texture, attributed to unique local microbial composition |

| Pain au Levain | France | Rustic bread, complex flavor, slightly dense crumb, made with a natural starter |

| Roggenbrot | Germany | Dark, dense rye bread, hearty flavor, long shelf life, made with sourdough |

| Borodinsky Bread | Russia | Sourdough rye bread, flavored with coriander and molasses, complex and slightly sweet flavor |

9. Common Sourdough Problems and Solutions: Troubleshooting Your Bake

Even experienced bakers encounter challenges with sourdough. Here are some common problems and their solutions:

9.1. Dough Not Rising

- Solution: Ensure your starter is active and bubbly. Adjust fermentation time based on room temperature and starter activity.

9.2. Dense, Gummy Crumb

- Solution: Increase fermentation time, ensure proper gluten development, and avoid over-proofing.

9.3. Too Sour

- Solution: Reduce fermentation time or use a higher fermentation temperature to favor lactic acid production over acetic acid.

9.4. Flat Loaf

- Solution: Ensure proper gluten development, shape the dough tightly, and avoid over-proofing.

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Dough Not Rising | Ensure starter is active, adjust fermentation time based on room temperature and starter activity. |

| Dense, Gummy Crumb | Increase fermentation time, ensure proper gluten development, avoid over-proofing; bake at a higher temperature to set the structure. |

| Too Sour | Reduce fermentation time, use a higher fermentation temperature to favor lactic acid production over acetic acid; use less starter in the dough. |

| Flat Loaf | Ensure proper gluten development, shape the dough tightly, avoid over-proofing; consider adding a small amount of commercial yeast to enhance rise. |

10. Answering Your Questions: Sourdough FAQs

Still have questions about sourdough? Here are some frequently asked questions:

10.1. Can I use whole wheat flour for my starter?

Yes, you can use whole wheat flour for your starter. It may actually help boost its activity due to the higher nutrient content.

10.2. How often should I feed my starter?

If you’re keeping your starter at room temperature, feed it once or twice a day. If you’re storing it in the refrigerator, you can feed it once a week.

10.3. How can I tell if my starter is active?

An active starter will be bubbly, have a pleasant sour aroma, and double in size after feeding.

10.4. What is the best temperature for fermenting sourdough?

The ideal fermentation temperature is between 72-78°F (22-26°C).

10.5. Can I make sourdough without a Dutch oven?

Yes, you can bake sourdough without a Dutch oven. You can use a baking stone or a sheet pan with a tray of water to create steam in the oven.

10.6. Why is my sourdough bread so hard?

Hard sourdough bread could be due to overbaking or not enough moisture during baking. Try reducing the baking time or adding more steam to the oven.

10.7. What does over-proofed dough look like?

Over-proofed dough will appear flat and deflated. It may also have a sour, unpleasant smell.

10.8. Is sourdough bread good for weight loss?

Sourdough bread can be part of a healthy weight loss plan due to its lower GI and improved digestion, but portion control is important.

10.9. Can I freeze sourdough bread?

Yes, you can freeze sourdough bread. Wrap it tightly in plastic wrap and then in foil or place it in a freezer bag.

10.10. What can I do with sourdough discard?

Sourdough discard can be used in various recipes, such as pancakes, waffles, crackers, and even cakes.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Can I use whole wheat flour for my starter? | Yes, it can boost starter activity due to higher nutrient content. |

| How often should I feed my starter? | Room temp: once/twice a day; Refrigerator: once a week. |

| How can I tell if my starter is active? | Bubbly, pleasant sour aroma, doubles in size after feeding. |

| Best temperature for fermenting? | 72-78°F (22-26°C). |

| Can I make it without a Dutch oven? | Yes, use a baking stone or sheet pan with water for steam. |

| Why is it so hard? | Overbaking or not enough moisture during baking; reduce baking time or add steam. |

| What does over-proofed dough look like? | Flat, deflated, sour smell. |

| Is it good for weight loss? | Can be part of a healthy plan, but portion control is important. |

| Can I freeze it? | Yes, wrap tightly in plastic wrap and foil or place in a freezer bag. |

| What can I do with discard? | Use in pancakes, waffles, crackers, cakes, and other recipes. |

Ready to embark on your sourdough adventure? For more in-depth guides, troubleshooting tips, and delicious sourdough recipes, visit FOODS.EDU.VN today! We offer a wealth of information to help you master the art of sourdough baking and unlock its many benefits.

Contact Us:

- Address: 1946 Campus Dr, Hyde Park, NY 12538, United States

- WhatsApp: +1 845-452-9600

- Website: FOODS.EDU.VN

Start exploring the delicious and nutritious world of sourdough with foods.edu.vn!