1. Introduction

In today’s fast-paced world, lifestyle-related diseases like insulin resistance, heart disease, and hypertension are increasingly prevalent. Fortunately, simple dietary changes can make a significant impact. Among these, incorporating foods that boost nitric oxide (NO) production stands out as a powerful strategy. Rich in nitrates and nitrites, certain foods can naturally enhance your body’s NO levels, offering a proactive approach to preventing and managing these conditions. This article delves into the science behind Nitric Oxide Foods, exploring how they work, their safety, and their remarkable benefits for overall health. We’ll uncover how these dietary powerhouses can contribute to a healthier, more resilient you.

2. The Science of Nitric Oxide and Diet: How Food Becomes a Health Booster

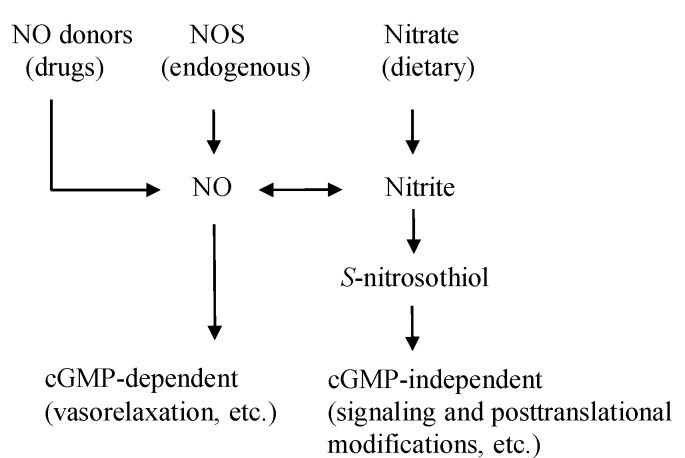

Nitric oxide (NO) is a vital molecule produced in your body, playing a key role in various physiological processes, including blood vessel dilation, nerve signaling, and immune defense. While your body naturally generates NO through the L-arginine-NOS pathway, there’s another crucial route: the nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway, significantly influenced by your diet (Figure 1). Certain foods, particularly vegetables, are packed with nitrates, which your body cleverly converts into nitrite and then into NO.

Figure 1: Diverse pathways of Nitric Oxide production in the body, highlighting the dietary influence.

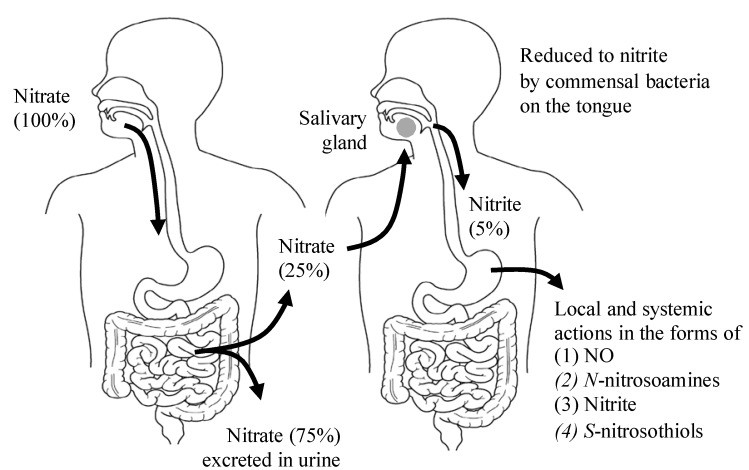

Green leafy vegetables like spinach, beets, and lettuce are nutritional stars when it comes to nitrate content (Table 1). In fact, vegetables contribute to the majority of our daily nitrate intake. When you consume these nitric oxide foods, your body efficiently processes them. Dietary nitrate is absorbed, and a portion is cleverly directed to the salivary glands. In your mouth, beneficial bacteria on your tongue convert nitrate into nitrite. As this nitrite-rich saliva is swallowed, it enters the acidic environment of the stomach, where it’s further converted into nitric oxide and other beneficial nitrogen compounds. This process significantly boosts NO levels in the body.

Table 1: Nitrate and Nitrite Concentrations in Common Nitric Oxide Foods

| Food Product | Nitrate Concentration (mg/100g) | Nitrite Concentration (mg/100g) |

|---|---|---|

| High Nitrate Vegetables | ||

| Beets | 275.6 (Range: 168–359) | 1.00 (Range: 0.21–2.98) |

| Spinach | 233.3 (Range: 53.5–366) | 0.70 (Range: 0.0–1.29) |

| Radishes | 168.0 (Range: 76.4–250) | 0.01 (Range: 0.0–0.1) |

| Celery | 154.4 (Range: 31.6–332) | 0.16 (Range: 0.0–0.52) |

| Lettuce | 85.0 (Range: 7.9–217.1) | 0.06 (Range: 0.001–0.97) |

| Iceberg Lettuce | 78.6 (Range: 34.7–108) | 0.02 (Range: 0.0–0.17) |

| Moderate Nitrate Vegetables | ||

| Mushroom | 59.0 (Range: 1.9–8.5) | 0.80 (Range: 0.0–3.8) |

| Cabbage | 57.3 (Range: 19.3–97.6) | 0.24 (Range: 0.0–1.26) |

| Broccoli | 39.4 (Range: 2.9–114) | 0.06 (Range: 0.001–0.95) |

| Green Beans | 38.6 (Range: 16.5–61.1) | 0.05 (Range: 0.0–0.25) |

| Lower Nitrate Foods | ||

| Strawberries | 17.3 (Range: 10.5–29.3) | 0.20 (Range: 0.0–0.71) |

| Banana | 13.7 (Range: 8.8–21.4) | 0.21 (Range: 0.0–0.95) |

| Green Pepper | 3.3 (Range: 0.8–5.5) | 0.04 (Range: 0.0–0.3) |

This ingenious entero-salivary pathway (Figure 2) ensures a continuous supply of NO, contributing to various health benefits throughout your body. Factors like antibacterial mouthwash can disrupt this process, highlighting the importance of maintaining a healthy oral microbiome for optimal NO production.

Figure 2: The Entero-Salivary Pathway: How Nitric Oxide Foods Deliver NO to Your Body

The nitrite produced from nitric oxide foods doesn’t just stay in the stomach; it enters your bloodstream and reaches peripheral tissues, including muscles. Here, it acts like a messenger, exerting NO-like activity. Interestingly, while acute intake of nitric oxide foods quickly boosts plasma nitrite levels, consistent, long-term consumption leads to increased nitrate and S-nitrosylated products in tissues (Table 2). This suggests that your body adapts to chronic intake, ensuring a steady supply of NO benefits.

Table 2: Impact of Dietary Nitrate on Tissue Nitrite/Nitrate Levels and Health Outcomes in Animal Models

| Animal Model | Dietary Nitrate | Tissues | Effects of Dietary Nitrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension Rat (High-Salt Diet) | 0.1 mM and 1 mM nitrate/kg/day (8–11 weeks) | Kidney, Heart, Liver | Increased nitrate & nitrosylation; Reduced oxidative stress, renal injury, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy & fibrosis. |

| Mice (Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension) | 0.6 mM, 15 mM, 45 mM nitrate/L (3 weeks) | Lung | Increased nitrite & cGMP; Reduced pulmonary hypertension, vascular remodeling. |

| Rat (Hypoxic Heart Damage) | 0.7 mM/L nitrate (2 weeks) | Heart | Increased nitrate & nitrite; Improved metabolic abnormalities, myocardial energetics in hypoxic heart. |

Your body also has backup systems to convert nitrite to NO, especially in low-oxygen conditions. Enzymes and proteins in muscles and tissues can step in to produce NO from nitrite when needed. This is particularly beneficial during exercise when muscles need more oxygen and blood flow.

3. Are Nitric Oxide Foods Safe? Understanding the Facts

Concerns about the safety of nitrates and nitrites have been raised, particularly regarding methemoglobinemia in infants and potential links to cancer. It’s true that high nitrate levels in drinking water can be dangerous for infants, leading to “blue baby syndrome.” However, this is primarily linked to bacterial contamination, not nitrates themselves. Regulatory bodies like the EPA have set safe limits for nitrate in drinking water, but these are often considered overly cautious.

Regarding cancer, the concern stems from the potential for nitrite to form nitrosamines, which are carcinogenic. However, this is more likely to occur with high intakes of processed meats, which contain added nitrites as preservatives. Nitrates and nitrites from vegetables, especially when consumed with antioxidants like vitamin C and polyphenols also found in vegetables and fruits, are less likely to form nitrosamines. In fact, the overall scientific consensus is that dietary nitrate from vegetables is not carcinogenic and may even be protective against certain cancers.

It’s important to distinguish between naturally occurring nitrates in vegetables and nitrites added to processed meats. The health benefits of nitric oxide foods, primarily vegetables, far outweigh the theoretical risks. International health organizations have established Acceptable Daily Intakes (ADIs) for nitrate and nitrite, but typical vegetable-rich diets, even those high in nitrate vegetables, generally fall within safe ranges. In fact, diets like the DASH diet, rich in vegetables, can lead to nitrate intakes exceeding these ADIs, yet are associated with significant health benefits, further suggesting the safety and benefits of nitric oxide foods.

4. The Broad Spectrum Benefits of Nitric Oxide Foods for Lifestyle-Related Diseases

Lifestyle-related diseases are often characterized by reduced NO availability and increased oxidative stress. Nitric oxide foods offer a natural way to combat these imbalances and promote better health. By increasing NO bioavailability, these foods can improve cellular redox balance and positively impact various conditions.

4.1. Enhancing Insulin Sensitivity and Combating Insulin Resistance

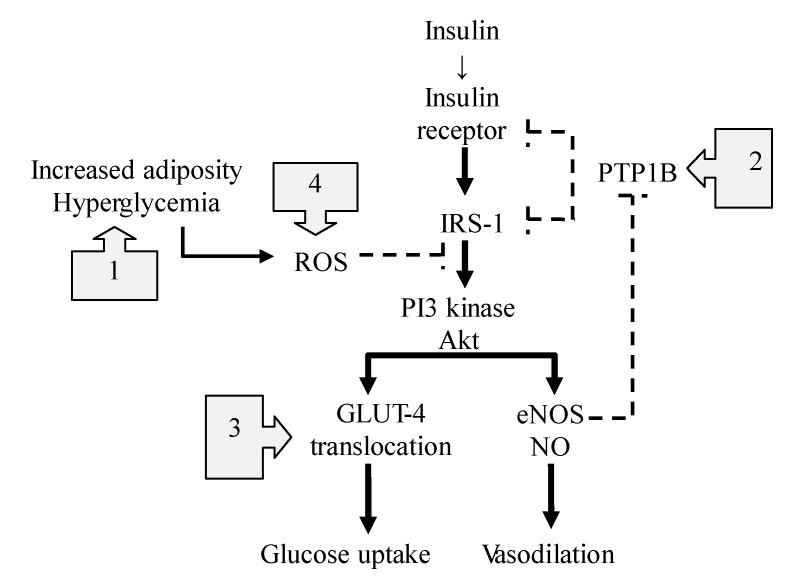

Insulin resistance, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, is often linked to impaired NO production. Nitric oxide plays a crucial role in insulin signaling, helping to regulate blood flow and glucose uptake in tissues (Figure 3). Nitric oxide foods can improve insulin sensitivity through multiple mechanisms:

- Reducing Inflammation: NO helps suppress TLR4-mediated inflammation, a key contributor to insulin resistance.

- Improving Insulin Signaling: NO enhances insulin’s effects by modulating protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTPB1), an enzyme that can hinder insulin signaling.

- Facilitating Glucose Uptake: NO promotes the translocation of GLUT4, a glucose transporter, to cell membranes, improving glucose uptake.

- Boosting Mitochondrial Function: NO can improve mitochondrial function and reduce mitochondrial ROS production, further enhancing insulin sensitivity.

Figure 3: Nitric Oxide’s Multifaceted Action in Improving Insulin Signaling Pathways

Studies have shown that dietary nitrate, readily available in nitric oxide foods, can improve insulin resistance in both humans and animals. By enhancing NO availability, these foods offer a promising dietary strategy to manage and prevent insulin resistance and related metabolic disorders.

4.2. Lowering Blood Pressure and Supporting Cardiovascular Health

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for heart disease. Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator, meaning it helps relax and widen blood vessels, leading to improved blood flow and reduced blood pressure. Consuming nitric oxide foods, rich in nitrates, can effectively lower blood pressure.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the blood pressure-lowering effects of dietary nitrate, particularly from beetroot juice and leafy green vegetables. These foods increase plasma nitrite levels, which the body converts to NO, resulting in vasodilation and improved vascular function. Dietary nitrate has been shown to reduce both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and improve arterial stiffness, a key factor in age-related hypertension.

Furthermore, nitric oxide foods can protect against cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury, a condition that occurs when blood flow is restored to the heart after a period of blockage. NO helps reduce oxidative stress and cell damage during reperfusion, improving heart function and reducing infarct size. The consistent intake of nitric oxide foods can contribute significantly to long-term cardiovascular health and hypertension management.

4.3. Supporting Lung Health and Managing COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is often linked to oxidative stress and inflammation in the lungs. While some studies have explored potential negative effects of nitrites from processed meats on COPD risk, the evidence for nitric oxide foods, particularly vegetables, points towards potential benefits.

Nitric oxide plays a complex role in lung health. While excessive NO production from inflammation can be detrimental, NO derived from dietary nitrates can have protective effects. NO can help relax bronchial smooth muscles, reduce airway hyperresponsiveness, and possess anti-inflammatory properties relevant to COPD.

Emerging research suggests that dietary nitrate from sources like beetroot juice may improve exercise performance and reduce blood pressure in COPD patients. By improving mitochondrial efficiency and oxygen utilization, nitric oxide foods may offer supportive benefits for individuals with COPD, though more research is needed in this area.

4.4. Exploring the Complex Relationship with Cancer Risk

The relationship between dietary nitrate/nitrite and cancer is complex and often misunderstood. While nitrosamines, formed from nitrite reacting with amines, are carcinogenic, the context of nitrate and nitrite intake is crucial.

Nitrates from vegetables, the primary source of nitric oxide foods, are generally not considered carcinogenic. In the stomach, nitrite can form both nitrosamines (potentially harmful) and S-nitrosothiols (potentially beneficial). However, the presence of antioxidants like vitamin C and polyphenols in vegetables tends to favor S-nitrosothiol formation and reduce nitrosamine formation.

Epidemiological studies have not shown a consistent link between vegetable nitrate intake and increased cancer risk. In fact, some studies suggest an inverse association between vegetable consumption and certain cancers, such as gastrointestinal and colorectal cancers. The protective effects of vegetables, including their nitrate content, may be synergistic with other beneficial compounds present in these foods.

It’s important to differentiate between nitrates from vegetables and nitrites added to processed meats. While excessive consumption of processed meats may pose a cancer risk, nitric oxide foods, primarily vegetables and fruits, are not considered to be carcinogenic and may even offer protective benefits.

4.5. Promoting Bone Health and Preventing Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis, characterized by weakened bones, is influenced by lifestyle factors and hormonal changes. Nitric oxide plays a role in bone metabolism, with different types of NOS having varying effects. eNOS, a constitutive form of NOS, is important for osteoblast activity and bone formation.

Studies suggest that NO donors can have beneficial effects on bone health. Epidemiological data indicates that higher fruit and vegetable intake is associated with a protective effect against osteoporosis. While the specific mechanisms of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in preventing osteoporosis are still being investigated, nitric oxide foods may contribute to bone health, possibly through NO-mediated pathways that influence bone cell activity. Including nitric oxide foods as part of a balanced diet and healthy lifestyle may support bone density and reduce osteoporosis risk.

5. Conclusion: Embrace Nitric Oxide Foods for a Healthier Life

Nitric oxide foods, primarily vegetables rich in dietary nitrates, offer a natural and effective way to boost your body’s nitric oxide levels. Through the ingenious entero-salivary pathway, these foods deliver NO in various beneficial forms, contributing to a wide range of health benefits. From improving cardiovascular health and insulin sensitivity to potentially supporting lung and bone health, nitric oxide foods are a powerful tool in preventing and managing lifestyle-related diseases.

While concerns about nitrate and nitrite safety exist, the scientific evidence overwhelmingly supports the safety and benefits of consuming nitric oxide foods, particularly vegetables, as part of a balanced diet. Embracing a diet rich in these foods is a proactive step towards a healthier, more vibrant life. Make nitric oxide foods a cornerstone of your diet and unlock their potential to power up your health.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks for the financial supports from Josai University. The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Author Contributions

Jun Kobayashi wrote the manuscript. Kazuo Ohtake and Hiroyuki Uchida reviewed the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Ford, E.S.; Bergmann, M.M.; Kröger, J.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Weikert, C.; Boeing, H. Healthy living is the best revenge: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2] World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

[3] Dauchet, L.; Ferrières, J.; Arnault, N.; Moore, N.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Hercberg, S.; Amouyel, P.; Dallongeville, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4] He, F.J.; Nowson, C.A.; MacGregor, G.A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: Meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet 2006, 367, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5] Crowe, F.L.; Roddam, A.W.; Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Overvad, K.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Tjønneland, A.; Boeing, H.; Buijsse, B.; Nagel, G.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and mortality from ischaemic heart disease: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Oxford study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6] Johnsen, S.P.; Overvad, K.; Sørensen, H.T.; Tjønneland, A. Intake of fruit and vegetables and the risk of ischemic stroke in a cohort of Danish men and women. Stroke 2003, 34, e45–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7] Joshipura, K.J.; Ascherio, A.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.B.; Speizer, F.E.; Hennekens, C.H.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C. Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA 1999, 282, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8] Moncada, S.; Higgs, A. Nitric oxide and the vascular endothelium. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2006, 176, 213–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[9] Hess, D.T.; Stamler, J.S. S-nitrosylation and biological signaling. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 4589–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10] Bryan, N.S.; Martinez, J.R.; Feelisch, M.; McDonald, B.; McCallister, C.; Feelisch, R.W.; Hagen, T.M.; McMahon, T.J.; Stamler, J.S. Nitrite is a signaling molecule and regulator of gene expression in mammalian tissues. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11] Dalle-Donne, I.; Rossi, R.; Colombo, R.; Giustarini, D.; Milzani, A.; Gianni, P.; Rossi, G.; Santucci, R.; Prinetti, A.; Aldini, G.; et al. Protein S-glutathionylation in health and disease: Mechanisms and analytical methods. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 1059–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12] Poderoso, J.J.; Lisdero, C.L.; Riobó, N.A.; Carreras, M.C.; Cadenas, E.; Boveris, A. Nitric oxide inhibits mitochondrial respiration and increases superoxide radical production. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 328, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13] Brown, G.C. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial respiration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1411, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[14] Mannick, J.B.; Hausladen, A.; Liu, L.; Hess, D.T.; Zeng, M.; Miao, Q.X.; Nulton-Persson, A.C.; Anthony, C.; Green, N.E.; Miranda, K.M.; et al. Fas-induced caspase denitrosylation. Science 1999, 284, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15] Lundberg, J.O.; Gladwin, M.T.; Weitzberg, E. Strategies to increase nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16] Hord, N.G.; Tang, Y.; Bryan, N.S. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: The physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1S–10S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[17] Gangolli, S.D.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Feron, V.J.; Janzowsky, C.; Koeman, J.H.; Speijers, G.J.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Walker, R.; Wishnok, J.S. Nitrate, nitrite and N-nitroso compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 292, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[18] Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundqvist, A.G.; Sörqvist, B.; Rosén, R.; Arver, S.; Folkow, B.; Nathanson, C. Intragastric nitric oxide production in humans: Measurements in expelled air. Gut 1994, 35, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19] Munzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Mülsch, A. Explaining the phenomenon of nitrate tolerance. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[20] Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Cole, J.A.; Benjamin, N. Nitrate-reducing bacteria in human saliva. Nature 2004, 432, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[21] Tannenbaum, S.R.; Weisman, M.; Fett, D. The endogenous formation of nitrite in saliva. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1976, 14, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[22] Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Novel aspects of dietary nitrate and nitrite in human physiology. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2013, 33, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[23] Benjamin, N.; O’Driscoll, F.; Dougall, H.; Duncan, C.; Smith, L.; Golden, M.; McKenzie, H.; Lewis, M.J. Stomach NO synthesis. Nature 1994, 368, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[24] O’Leary, K.A.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Needs, P.W.; Shao, W.; Mellon, F.; Halliwell, B.; Williamson, G. Effect of flavonoids and vitamin C on nitrate-dependent nitric oxide production from Griffonia simplicifolia extract. Nitric Oxide 2004, 10, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[25] Sobhani, I.; Jonsson, E.; Färkkilä, M.; Håkansson, T.; Garcia, F.; Rafter, J.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Effects of gastric acidity and microflora on nitrite and N-nitroso compound formation in the human stomach. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 23, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[26] Modak, T.; Lupien, C.A.; Ardakani, S.; Song, Y.; Chambers, J.T.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Mowat, C.; Ahluwalia, A. Dietary nitrate modulates mucosal protection and healing in the stomach. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 308, G615–G624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[27] Li, H.; Xia, Y.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Effects of mouthwash on oral nitrate reduction and blood pressure. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28] Hord, N.G. Dietary Nitrates and Nitrites in Human Health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1S–2S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[29] Bryan, N.S.; Calvert, J.W.; Elrod, J.W.; Gundewar, S.; Lefer, D.J. Dietary nitrite rescues ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[30] Zweier, J.L.; Samouilov, A.; Kuppusamy, P. Non-enzymatic nitric oxide synthesis in biological systems. Implications for ischemia-reperfusion. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 11919–11922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[31] Cosby, K.; Partovi, K.S.; Crawford, J.H.; Patel, R.P.; Reiter, C.D.; Martyr, S.; Yang, B.K.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Schechter, A.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates hypoxic pulmonary vasculature. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[32] Stamler, J.S.; Jia, L.; Feelisch, M. Nitric oxide cycles between redox states: Metabolism and cytoprotection. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[33] Shiva, S.; Weber, T.J.; Patel, R.P.; Richardson, G.J.; Augustine, D.; Claycamp, C.; Maples, C.J.; Zhang, J.; Feelisch, M.; Feelisch, M.; et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing myoglobin are protected from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[34] Godber, B.L.; Doel, J.J.; Hider, R.C.; Wilson, M.T.; Ford, N.L.; Feelisch, M.; Butler, A. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide catalyzed by xanthine oxidoreductase. Evidence for a one-electron mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 7757–7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[35] Ferguson, S.K.; Hirai, D.M.; Copp, S.W.; Holdsworth, C.T.; Allen, J.D.; Jones, J.H.; Musch, T.I.; Paterson, P.G.; Haykowsky, M.J.; доме, D.C. Microvascular oxygen pressures in exercising muscles of old rats: Effect of dietary nitrate supplementation. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[36] Larsen, F.J.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O.; Ekblom, B. Effects of dietary nitrate on oxygen cost during exercise. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2007, 191, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[37] Carlström, M.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Mechanisms underlying blood pressure lowering by dietary inorganic nitrate. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2013, 209, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[38] Al-Saud, H.B.; Drummond, G.R.; Jelinic, M.; Markos, F.; McGrath, K.C.; Sobey, C.G.; Rye, K.A.; Stocker, R.; Bursill, C.A. Dietary nitrate reduces features of experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[39] Baliga, R.S.; Lee, J.W.; Villamena, F.A.; Gambhir, S.; Rodrigues, A.C.; четене, A.L.; Feelisch, M.; Khaper, N.; Park, Y.B.; Shiva, S.; et al. Dietary nitrate prevents heart failure in the spontaneously hypertensive heart failure-prone rat. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H2109–H2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[40] Hess, D.T.; Matsumoto, A.; Kim, S.O.; Marshall, H.E.; Stamler, J.S. Protein S-nitrosylation: Specificity and cellular regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[41] Greer, F.R.; Shannon, M. Nitrate and methemoglobinemia: Reevaluation of the hazard to infants. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 784–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[42] Comly, H.H. Cyanosis in infants caused by nitrates in well water. JAMA 1945, 129, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[43] Avery, A.A. Nitrate and nitrite in drinking water: Exposure, toxicology, and recommendations. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 1999, 5, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[44] EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Nitrate in vegetables. EFSA J. 2008, 689, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

[45] Health Protection Agency (HPA). Nitrate and Nitrite in Drinking Water. 2009. Available online: http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1230470447155 (accessed on 22 July 2015). [Google Scholar]

[46] Appel, L.J.; Moore, T.J.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Vogt, T.M.; Cutler, J.A.; Windhauser, M.M.; et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[47] Evans, J.L.; Goldfine, I.D. The molecular basis for insulin resistance: Linking obesity to diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[48] Dandona, P.; Aljada, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Mohanty, P.; Garg, R. Paradoxical elevation of nitric oxide and endothelin-1 and decrease in tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in obese subjects. Diabetes 2004, 53, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[49] Muniyappa, R.; Hall, G.; Kolodziej, T.L.; Isumi, G.; Ting, S.T.; Chen, H.; Abbasi, F.; Reaven, G.M.; Quon, M.J. Insulin resistance is associated with impaired microvascular nitric oxide synthase activity. Circulation 2007, 115, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[50] Muniyappa, R.; Quon, M.J. Insulin action and insulin resistance: Anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory effects. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 293, E1103–E1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[51] Styskal, R.; Van Eyk, J.E. Nitric oxide and insulin resistance. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2007, 46, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[52] Wang, P.; Katakam, P.V.; Nedelcu, J.; Madden, A.; Wang, J.; Mortensen, R.M.; Lusis, A.J.; Marsden, P.A.; Chakrabarti, S.; Rozakis-Adcock, M.; et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency promotes insulin resistance and lipid accumulation in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[53] Hsueh, W.A.; Quiñones, M.J. Role of endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 92, 10J–17J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[54] Hölscher, D.D.; Nyborg, N.C.B. Dietary nitrate and nitric oxide bioavailability: Implications for metabolic disease and type 2 diabetes. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2014, 17, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[55] Nyström, T.; Strassburger, K.; Behrendt, I.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Pavo, I.; Jansson, P.A.; Borén, J.; Machann, J.; Peter, A.; et al. Beetroot juice lowers human blood pressure due to a pure nitric oxide mechanism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[56] Larsen, F.J.; Ekblom, B.; Sahlin, K.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Effects of dietary nitrate on mitochondrial efficiency in humans. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[57] Ghosh, S.; Gollapudi, S.; Mootsik