The food pyramid is a visual tool representing the optimal number of servings a person should consume daily from each basic food group. Designed to guide individuals towards a balanced and healthy diet, it has evolved significantly since its inception. Let’s delve into the history, variations, and debates surrounding this widely recognized dietary guide.

Origins and Evolution of the Food Pyramid

The concept of the food pyramid wasn’t originally intended as a guide to balanced nutrition. It emerged from a need to manage food shortages. In 1943, during World War II, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) introduced the Basic 7 food guide to help Americans navigate food rationing. This guide categorized foods into seven groups, including bread and cereals, fruits and vegetables, and meat and poultry.

In the 1970s, Sweden faced rising food costs and sought to address the issue through dietary guidelines. The National Board of Health and Welfare proposed two food groups: “basic” and “supplementary.” However, this categorization was nutritionally flawed, as “supplementary” foods included essential items like fruits, vegetables, meat, and fish. They also experimented with a dietary circle resembling a cake divided into segments, but it lacked clear guidance on portion sizes.

Anna-Britt Agnsäter, an educator working for a Swedish grocery cooperative, developed the food pyramid in 1974. Published in the cooperative’s magazine, it divided foods into three levels:

- Bottom: Bread, grains, legumes, potatoes, and milk

- Middle: Fruits, vegetables, and juices

- Top: Eggs, meat, and fish

Agnsäter chose the pyramid shape to illustrate that the majority of one’s diet should consist of foods from the bottom level, with progressively smaller portions from the levels above. This visual representation quickly gained popularity, and other Nordic countries soon adapted their own versions.

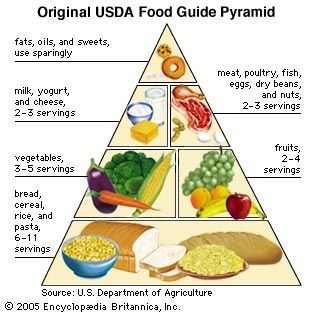

In 1992, the USDA introduced its own version of the food pyramid. It featured four levels:

- Bottom: Bread, cereal, rice, and pasta (6-11 servings per day)

- Second: Divided into Vegetable group (3-5 servings) and Fruit group (2-4 servings)

- Third: Milk, yogurt, and cheese (2-3 servings) and Meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts (2-3 servings)

- Top: Fats, oils, and sweets (to be eaten sparingly)

This USDA pyramid inspired the creation of similar guides for specific cuisines and diets, including Asian, Mediterranean, Latin American, vegetarian, and vegan options. Many countries worldwide, including Mexico, Chile, Panama, and the Philippines, adopted the pyramid structure. However, some countries opted for alternative visual representations to reflect cultural preferences or simply to offer a different perspective. Canada used a rainbow, Zimbabwe a square, Guatemala a family pot, and Japan the number 6. South Korea and China designed pagodas, while Australia created both pyramids and plates.

Modern Adaptations: From MyPyramid to MyPlate

In the early 21st century, the food pyramid underwent further transformations. In 2005, Japan introduced a spinning top design, inverting the traditional pyramid structure. In the same year, the USDA launched MyPyramid, featuring colorful stripes of varying widths to represent the relative proportions of different food groups. MyPyramid also incorporated a figure climbing stairs to emphasize the importance of physical activity.

MyPyramid, introduced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2005, represented the major food groups in coloured vertical bands. It was replaced in 2011 by a revised food guide graphic known as MyPlate.

In 2011, the USDA replaced MyPyramid with MyPlate, a simpler visual that depicts the basic food groups (fruits, grains, protein, and vegetables) as sections on a plate. The size of each section reflects the recommended dietary proportions for each food group. Unlike its predecessors, MyPlate does not include an exercise component or a specific section for fats and oils.

Global Variations and Dietary Considerations

The diverse range of food guides around the world, from rainbows and pots to pagodas and plates, reflects both cultural differences and varying nutritional recommendations. For example, while the USDA’s MyPlate emphasizes grains and vegetables in equal proportions with smaller portions of fruits and protein, Australia’s food pyramid prioritizes vegetables, legumes, and fruits, recommending they comprise 70% of daily food intake.

Mediterranean food guides often substitute cow dairy with yogurt and goat’s milk products due to the region’s high prevalence of lactose intolerance. Asian food guides incorporate soy products to replace nutrients typically found in dairy. The Asian Diet Pyramid emphasizes daily physical exercise and places rice, noodles, breads, millet, corn, and other whole grains at its base.

In India, the recommended food pyramid prioritizes cereals, grains, and milk, followed by fruits and vegetables, then meat, eggs, fish, salt, and oils in moderation, and lastly, sweets and junk food sparingly. This pyramid also advises against alcohol and tobacco consumption.

Criticisms and Debates

Despite its widespread use, the food pyramid has faced criticism for oversimplifying the complexities of a healthy diet. The USDA’s 1992 pyramid, for instance, has been criticized for not adequately educating people about the different types of carbohydrates and their nutritional profiles.

Furthermore, foods often contain a mix of nutrients, which is not always reflected in the food pyramid. For example, rice contains some protein, contributing to daily protein intake.

The placement of fats at the top of food pyramids has also been a point of contention. This categorization fails to distinguish between healthy unsaturated fats and less healthy saturated fats. This has sometimes led to the misconception that all fats should be avoided, even though some fat intake is essential for overall health.

Conclusion

The food pyramid has undergone significant evolution, reflecting changing nutritional understanding and cultural adaptations. While it serves as a useful visual guide to balanced eating, it’s important to remember that it’s a simplification of a complex topic. Individuals should consider consulting with nutrition professionals for personalized dietary advice that takes into account their specific needs and health conditions. By understanding the history, variations, and limitations of the food pyramid, we can make more informed choices about our diets and strive for healthier lifestyles.